The Transformative Influence of Alchemy on Art

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

The Transformative Influence of Alchemy on Art

Rather than an occult secret, alchemy is revealed in The Art of Alchemy at the Getty Center to be a prominent force in everything from medicine to color.

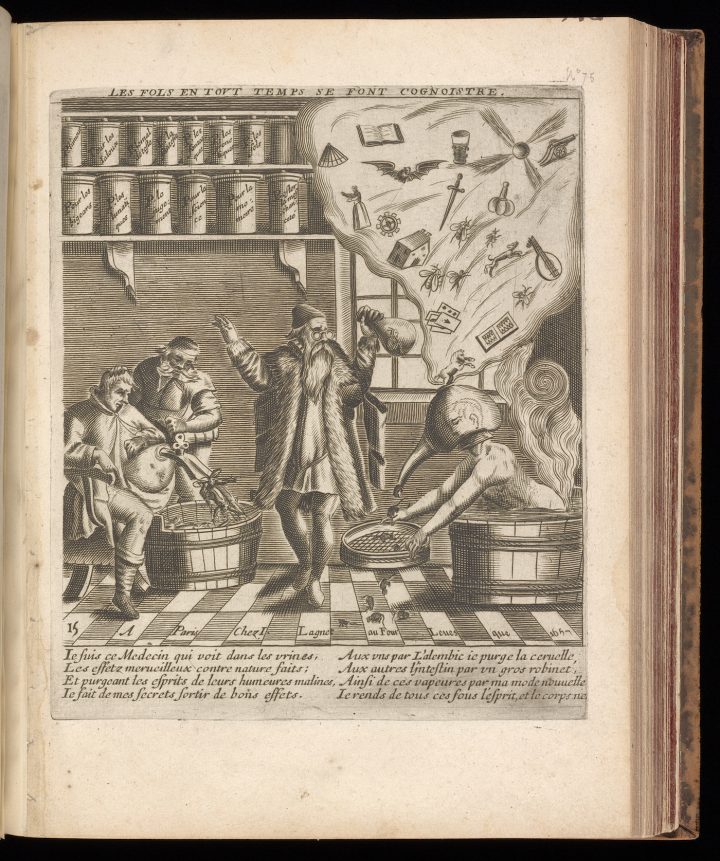

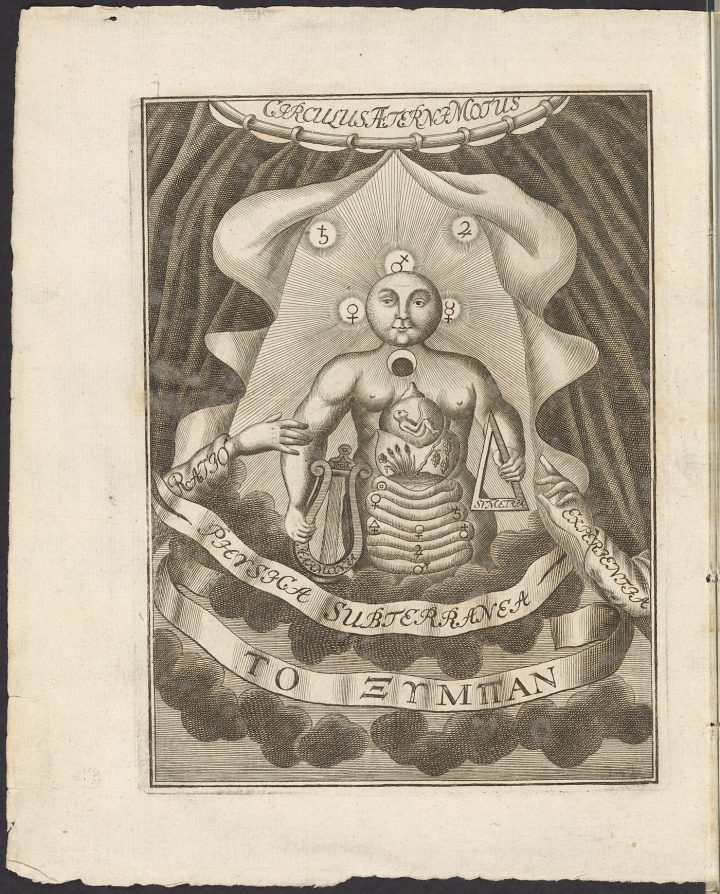

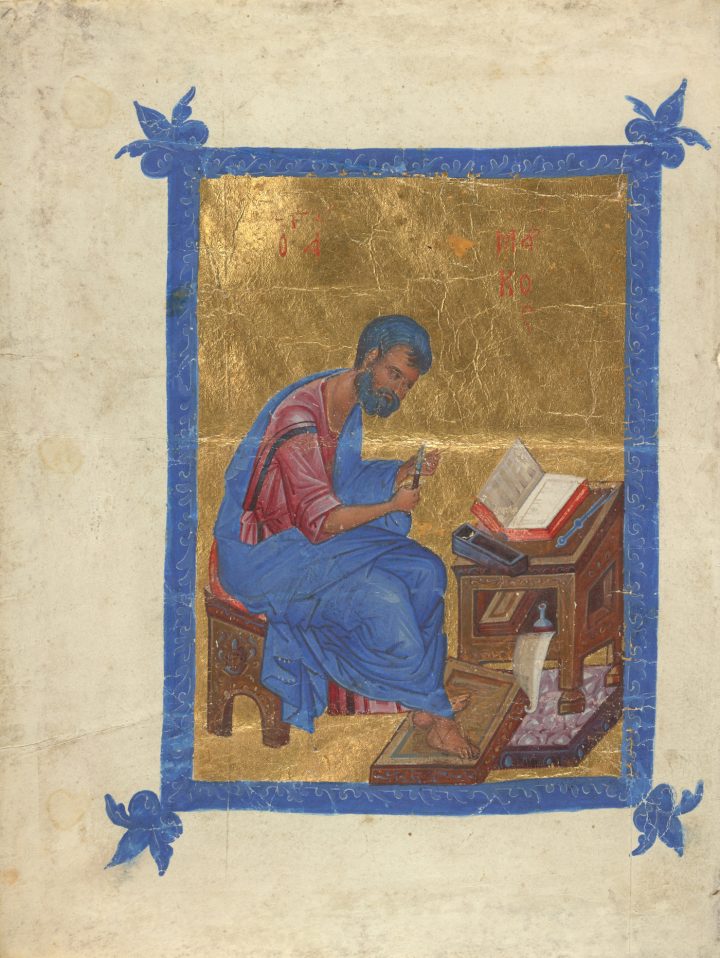

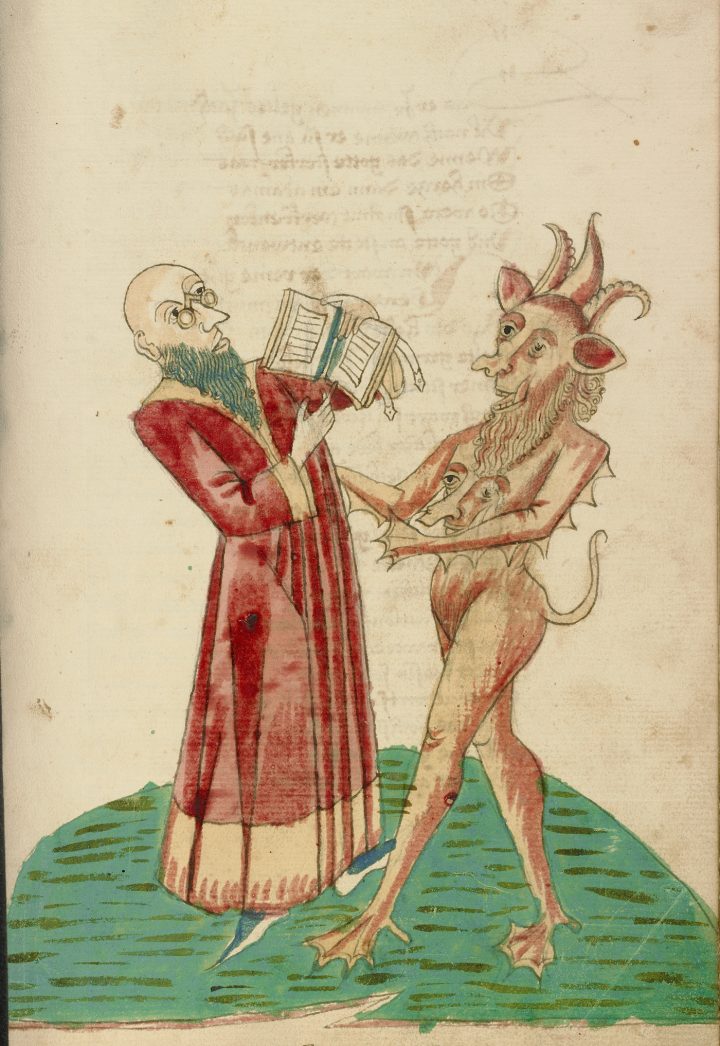

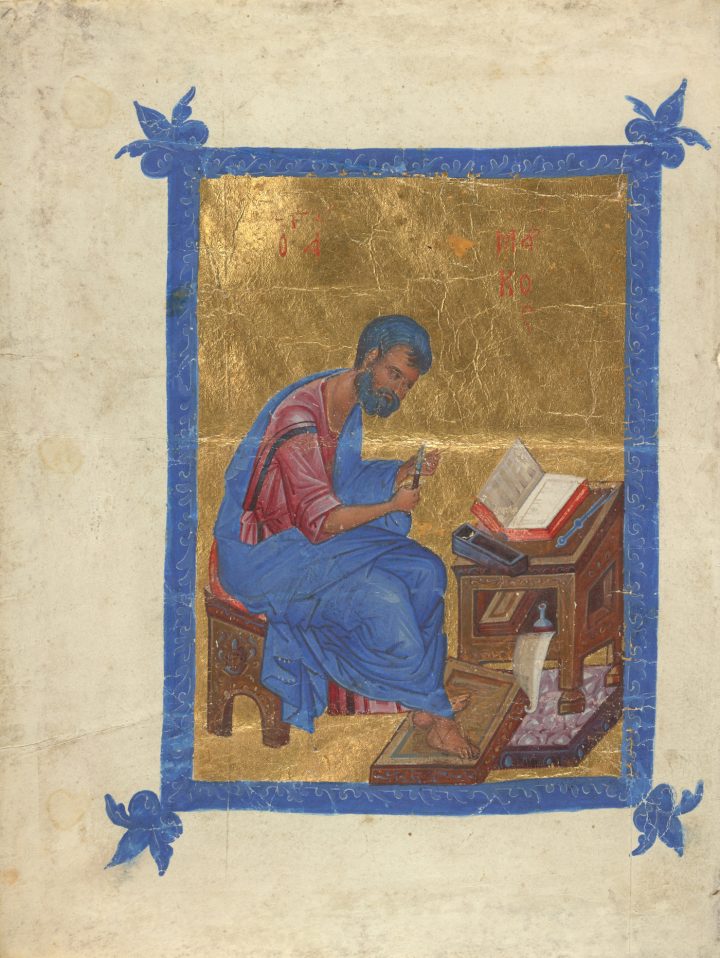

The “Great Art,” as it was often proclaimed in medieval Europe, was not the illuminated manuscript or religious stone carving; it was alchemy. The Art of Alchemy at the Getty Center in Los Angeles explores how the act of changing materials into new forms was not just an obscure practice, but an important part of culture.

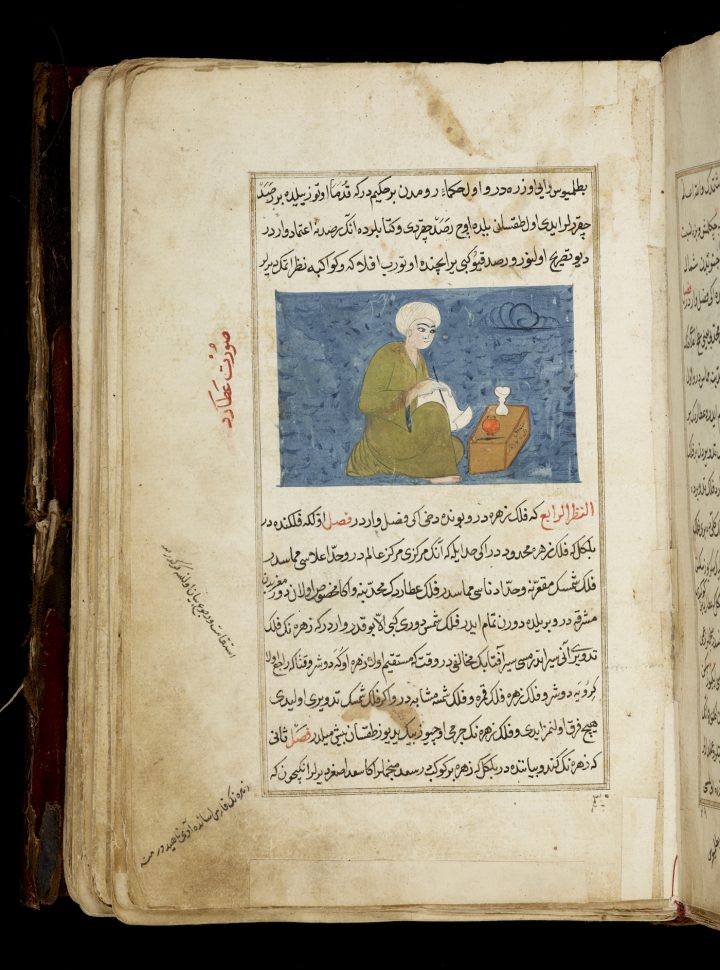

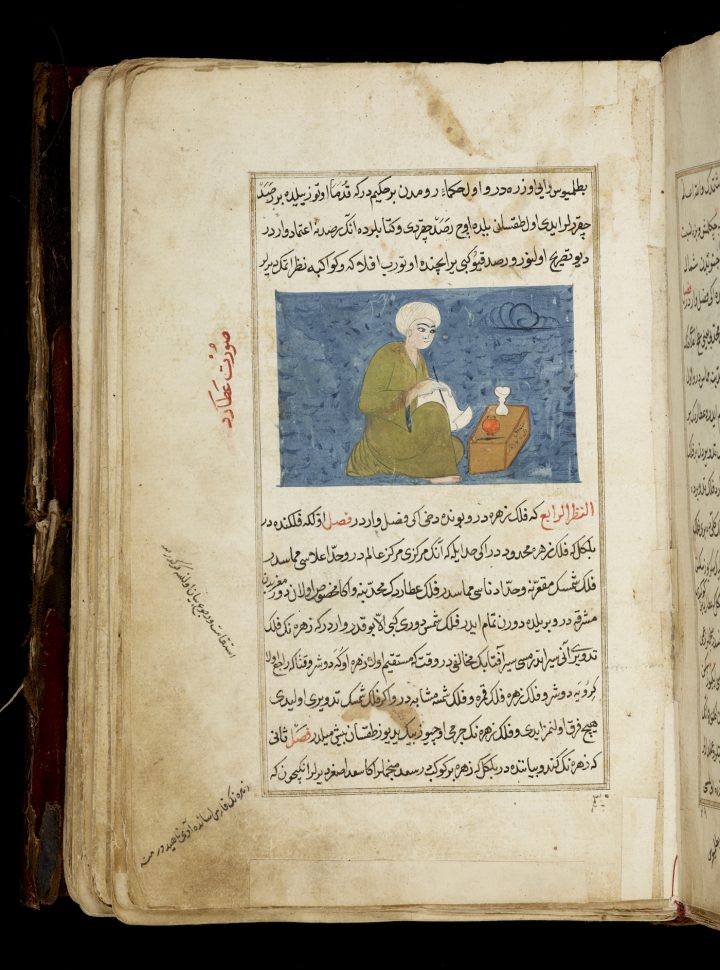

“I realized that there not only hadn’t been a show that looked at the pivotal role that alchemy played in the relationship between art and nature from antiquity onwards, but also the non-European aspect, and how important that was,” curator David Brafman told Hyperallergic. The Getty organized The Art Of Alchemyin partnership with theStaatliche Museen zu Berlin, where it will travel next year.

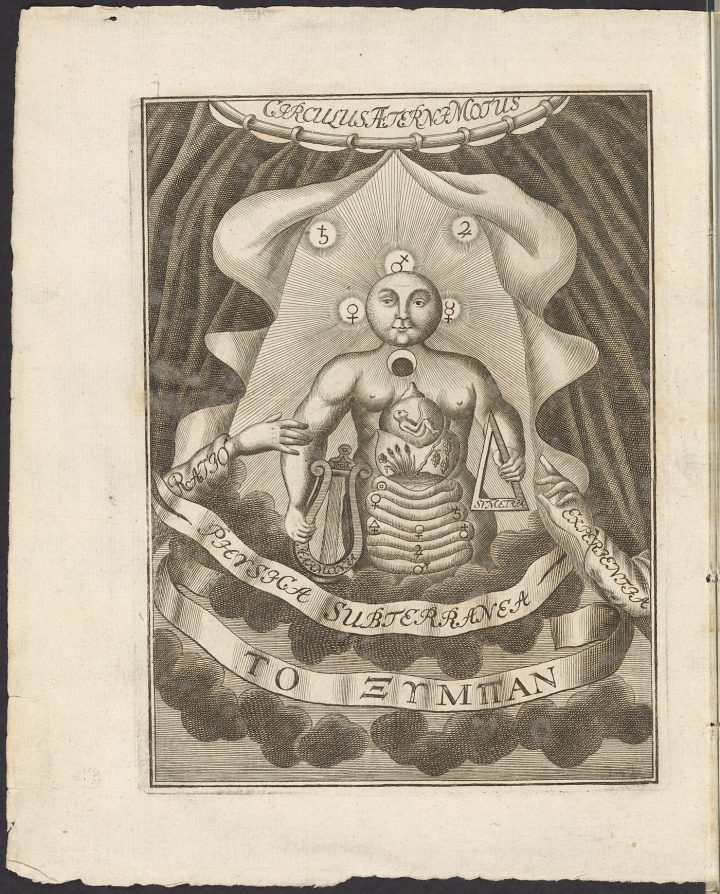

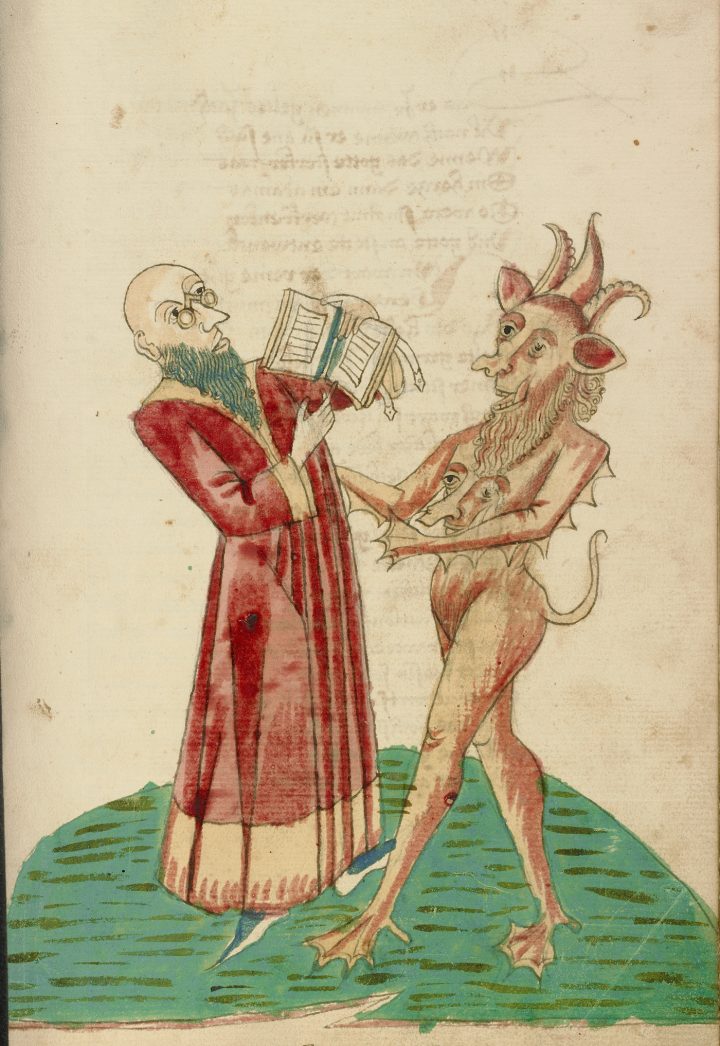

Brafman, an associate curator of rare books, worked with Rhiannon Knol to find over 100 objects from across the collections of the Getty Research Instituteand the J. Paul Getty Museum “that manifested the application of alchemical techniques to art,” going back to the 3rd century BCE. They discovered everything from Renaissance-era books that illustrate divine creation as a metaphor for art making, to the 20-foot long “Ripley Scroll” from the 18th century that features curious alchemical symbolism, including the “philosophers’ stone,” said to have the power to transform materials, like mercury into gold.

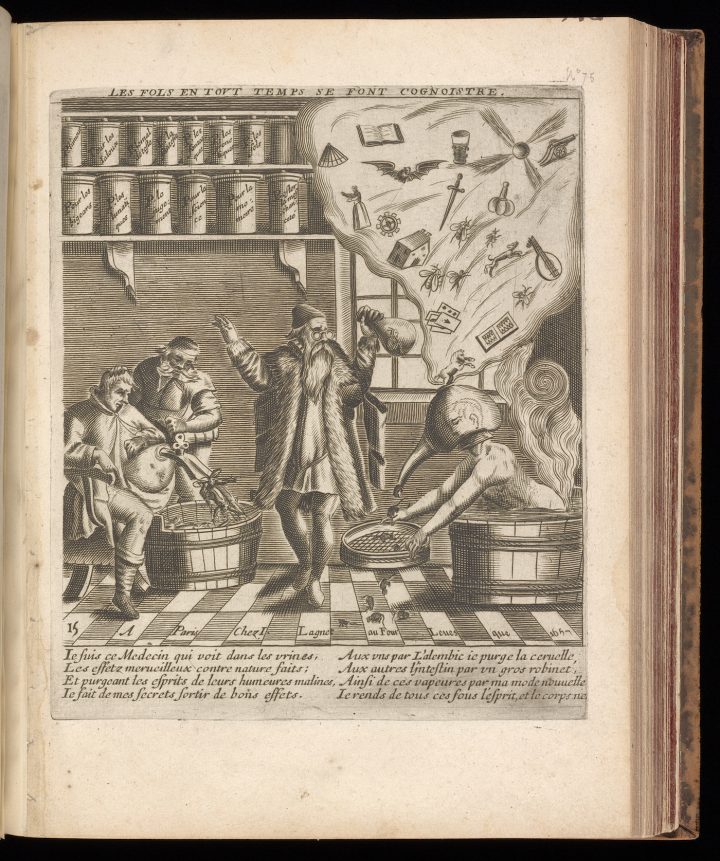

Alchemical techniques vital to the emergence of synthetic color are also considered. A very early example is a second-century mummy portrait created with red lead pigment. This theme is further examined in the concurrent The Alchemy of Color in Medieval Manuscripts at the Getty Center. “Something I kept coming across was alchemists supporting themselves with both an art industry and a pharmaceutical industry,” Brafman said. “The making of art and drugs is closely allied.”

This manipulation of nature into the synthetic is brought up to the present in The Art of Alchemy, with companies like Bayer creating colors from petroleum products alongside their pharmaceuticals. Whether glassmaking, metallurgy, or these chemical creations, alchemy is revealed to be everywhere. “Alchemy was called an art, and it’s the one that replicates nature without just trying to reproduce it,” Brafman said, emphasizing that it “straddles art, medicine, and philosophy.”

The Art of Alchemy continues at the Getty Center’s Getty Research Institute (1200 Getty Center Drive, Los Angeles) through February 12, 2017.

The “Great Art,” as it was often proclaimed in medieval Europe, was not the illuminated manuscript or religious stone carving; it was alchemy. The Art of Alchemy at the Getty Center in Los Angeles explores how the act of changing materials into new forms was not just an obscure practice, but an important part of culture.

“I realized that there not only hadn’t been a show that looked at the pivotal role that alchemy played in the relationship between art and nature from antiquity onwards, but also the non-European aspect, and how important that was,” curator David Brafman told Hyperallergic. The Getty organized The Art Of Alchemyin partnership with theStaatliche Museen zu Berlin, where it will travel next year.

Brafman, an associate curator of rare books, worked with Rhiannon Knol to find over 100 objects from across the collections of the Getty Research Instituteand the J. Paul Getty Museum “that manifested the application of alchemical techniques to art,” going back to the 3rd century BCE. They discovered everything from Renaissance-era books that illustrate divine creation as a metaphor for art making, to the 20-foot long “Ripley Scroll” from the 18th century that features curious alchemical symbolism, including the “philosophers’ stone,” said to have the power to transform materials, like mercury into gold.

Alchemical techniques vital to the emergence of synthetic color are also considered. A very early example is a second-century mummy portrait created with red lead pigment. This theme is further examined in the concurrent The Alchemy of Color in Medieval Manuscripts at the Getty Center. “Something I kept coming across was alchemists supporting themselves with both an art industry and a pharmaceutical industry,” Brafman said. “The making of art and drugs is closely allied.”

This manipulation of nature into the synthetic is brought up to the present in The Art of Alchemy, with companies like Bayer creating colors from petroleum products alongside their pharmaceuticals. Whether glassmaking, metallurgy, or these chemical creations, alchemy is revealed to be everywhere. “Alchemy was called an art, and it’s the one that replicates nature without just trying to reproduce it,” Brafman said, emphasizing that it “straddles art, medicine, and philosophy.”

The Art of Alchemy continues at the Getty Center’s Getty Research Institute (1200 Getty Center Drive, Los Angeles) through February 12, 2017.

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Comments

Post a Comment