- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

How Rodin Shaped Rilke as a Young Poet

Who knew that Rodin in his 60s met, inspired, and shaped Rilke in his 20s?

How Rodin Shaped Rilke as a Young Poet

Who knew that Rodin in his 60s met, inspired, and shaped Rilke in his 20s?

I

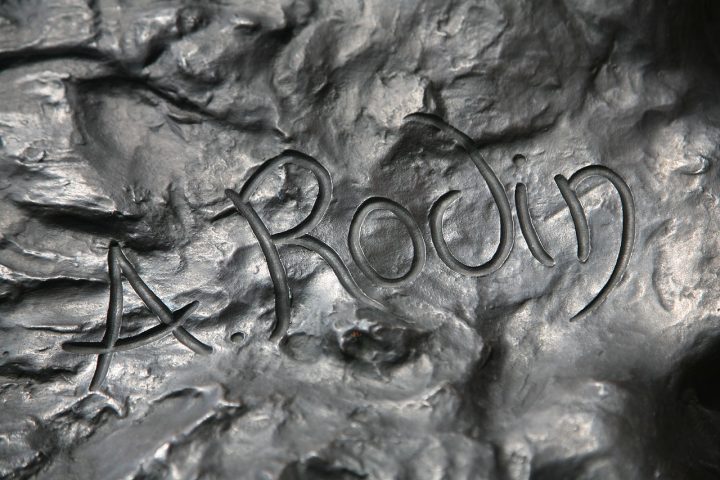

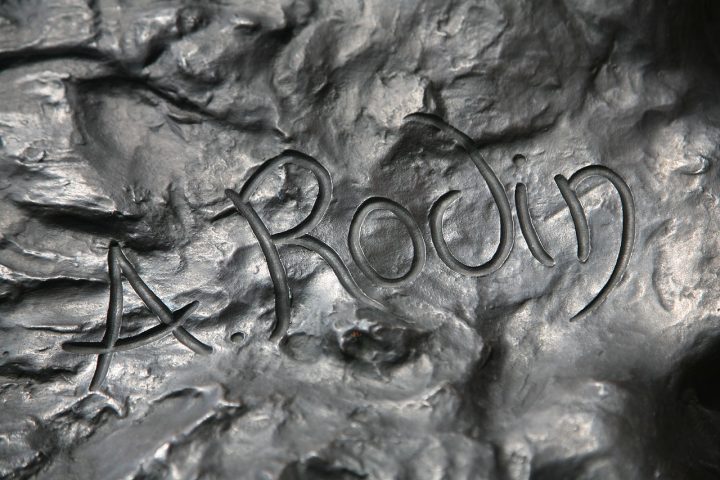

t mi

t mi ght seem strange to open this review with Auguste Rodin‘s signature on his sculpture “The Thinker.” But, the graceful curl of each letter amidst rough textures hints at Rodin’s lavish relationship with language. And it was contagious. A surprising new book reveals how Rodin’s way with words inspired Rainer Maria Rilke as a young poet.

ght seem strange to open this review with Auguste Rodin‘s signature on his sculpture “The Thinker.” But, the graceful curl of each letter amidst rough textures hints at Rodin’s lavish relationship with language. And it was contagious. A surprising new book reveals how Rodin’s way with words inspired Rainer Maria Rilke as a young poet.

t mi

t mi ght seem strange to open this review with Auguste Rodin‘s signature on his sculpture “The Thinker.” But, the graceful curl of each letter amidst rough textures hints at Rodin’s lavish relationship with language. And it was contagious. A surprising new book reveals how Rodin’s way with words inspired Rainer Maria Rilke as a young poet.

ght seem strange to open this review with Auguste Rodin‘s signature on his sculpture “The Thinker.” But, the graceful curl of each letter amidst rough textures hints at Rodin’s lavish relationship with language. And it was contagious. A surprising new book reveals how Rodin’s way with words inspired Rainer Maria Rilke as a young poet.

Who knew that Rodin in his 60s met, inspired, and shaped Rilke in his 20s? Nowadays, it would be temping to call Rodin a mentor. The poet and the sculptor actually lived and worked together, spent hours conversing, and forged a special bond. Up until now, this connection was a mere footnote. At long last, Rachel Corbett, who edits Modern Painters, wrote the book this story deserves.

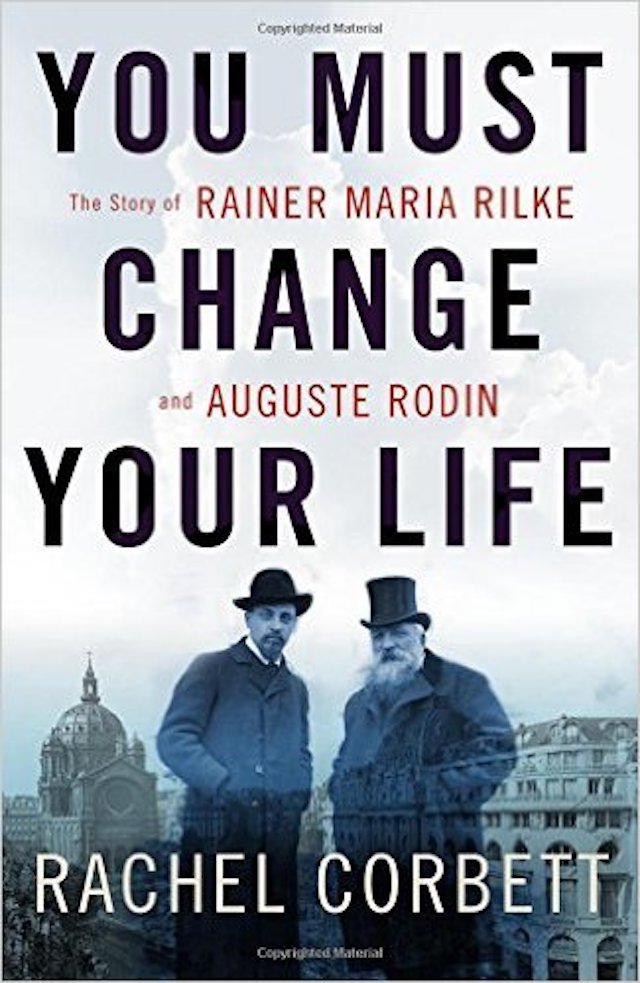

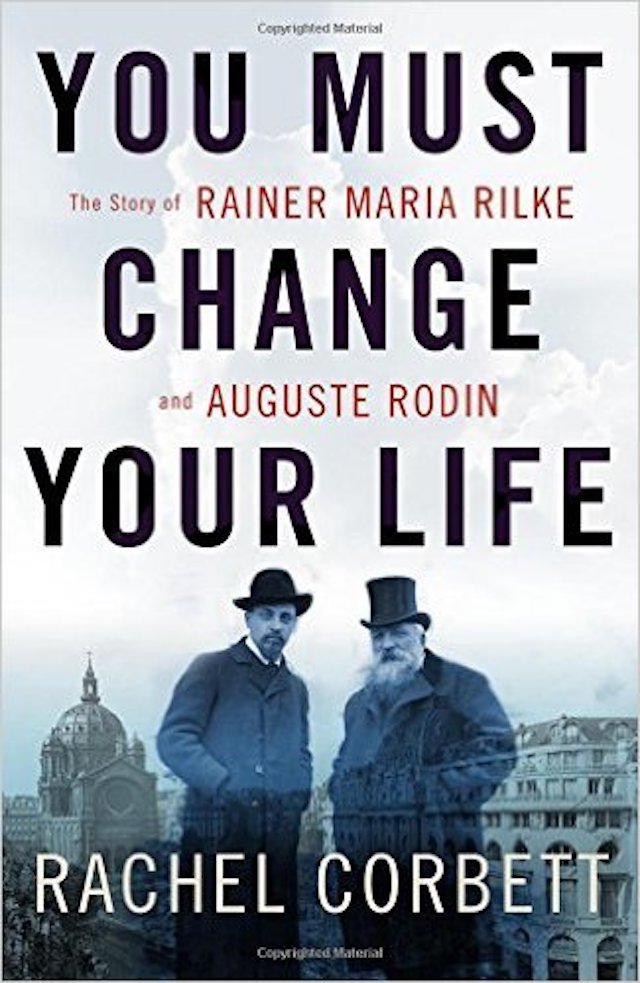

A riveting narrative unfolds in You Must Change Your Life: The Story of Rainer Maria Rilke and Auguste Rodin (W.W. Norton & Company) about bridging the generation gap. Corbett’s book is not only a case study in how a young poet learned from a renowned sculptor, but how Rodin found a way to connect with Rilke and a younger generation.

Corbett painstakingly researched how their lives intersected. Thirty-one pages of scholarly endnotes fastidiously anchor each assertion in a primary source. Nevertheless, the book moves along at a graceful fast clip; Corbett writes sharp prose that gets to the point.

Getting to the point wasn’t exactly Rilke’s forte. It may not be fair to expect that of any poet, especially one born in 1875 and swimming in the currents of the Symbolists. Rilke’s flowery — and daresay twee — verses do not jive with today’s tastes for cut-and-dry clarity, blasé irony, and Tweet-able brevity. But that’s precisely why Rilke is enjoying somewhat of a posthumous comeback. He offers what Twitter can’t.

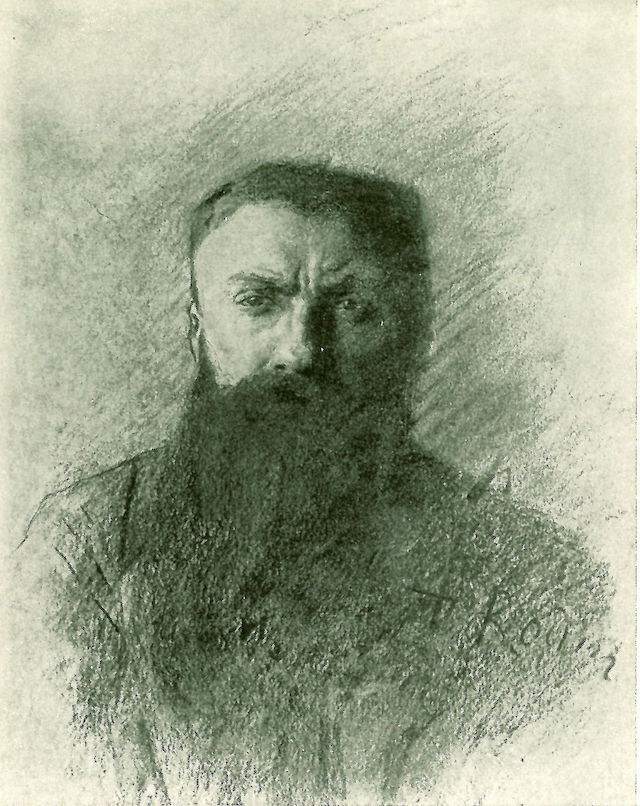

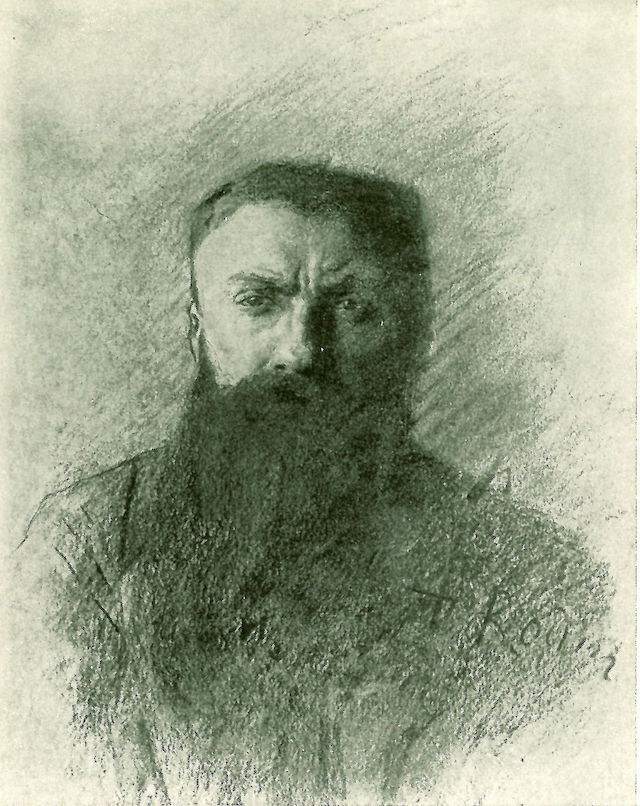

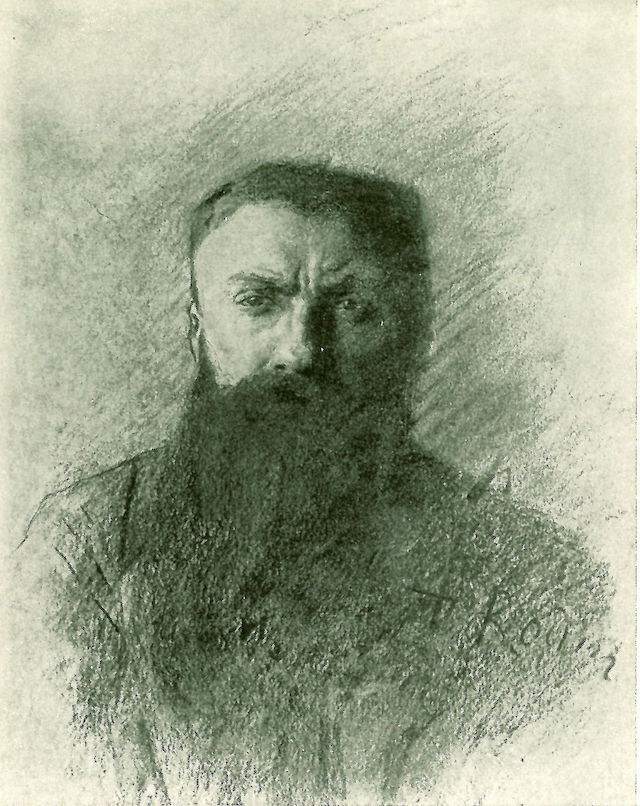

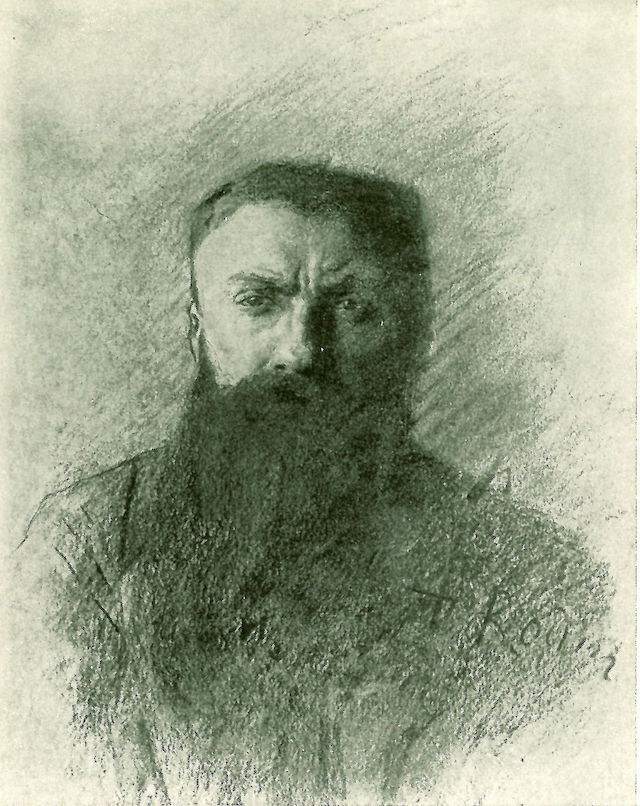

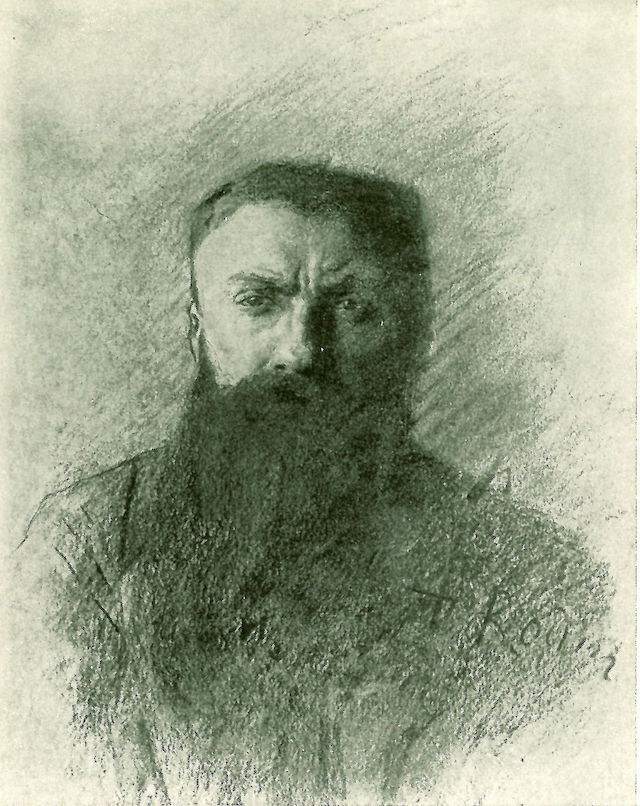

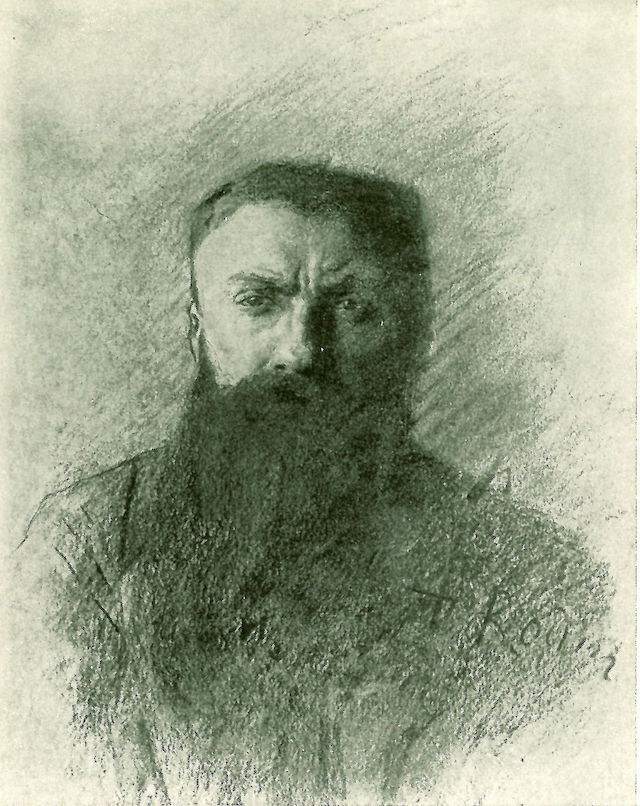

But why did aging Rodin in his 60s capture Rilke’s imagination at the turn of the last century? It’s hard to see at first. What made Rodin radical then is no longer radical today. In his “Self-Portrait” (1890), Rodin grimaces amidst rough marks. The picture emblematizes how Rodin heralded raw and unpolished sculptures that were strikingly modern. It was a breath of fresh air since most of early-19th-century sculpture was smooth, neoclassical, and to be harshly honest, predictably dainty. Charles Baudelaire lamented this nadir in 1846 when he wrote his provocative essay “Why Sculpture is Boring.” Rodin went on to prove Baudelaire wrong. He showed how sculpture could be modern with distorted, coarse, rough textures. Rodin knocked the idealized body off its pedestal. And the modern sculptors that came after him saw no reason to put it back.

The pair first met outside Paris on Rodin’s country estate in September of 1902. Rilke, 26, took on a project as an art critic to write a German monograph on Auguste Rodin, at the time 61. Neither probably expected they would hit it off as much as they did. But long talks about art, and how to cultivate a work ethic bonded them together. Ten days into his initial stay on Rodin’s estate, Rilke wrote Rodin an affectionate letter confessing their dialogue’s intense effect. Rodin offered the young poet an open invitation to observe his studio for the next four months. During that time, Rilke not only gleaned insights for his monograph, but discovered how to be a better poet.

Three years later in September of 1905, Rilke took a job as Rodin’s assistant and lived with him full-time on his country estate. For the first time, Rodin’s correspondence was prompt and his files organized. Rilke relished more long talks with Rodin and the book is filled with examples of how Rodin stimulated the poet during this period of employment and intense dialogue.

One of the more amusing examples is how Rodin said good night to Rilke. Rather than “bonne nuit,” Rodinwould say, “bon courage,” roughly translated to “show courage” or “have good courage,” but this idiomatic expression is hard to translate. While an unusual way to say good night, Rodin was trying to telegraph to Rilke that he would need to be courageous as he prepared for the next day’s inevitable challenges.

Predictably, the honeymoon didn’t last forever. A row over a letter Rilke wrote to one of Rodin’s contacts without permission in April 1906 aroused Rodin’s suspicion, so he fired Rilke. But an indelible impression was nevertheless left on the poet.

An echo of Rodin can be heard in letters Rilke wrote to a young poet Franz Kappus. Their correspondence began in February 1903, just after Rilke first encountered Rodin in the fall of 1902, and it carried on for several years. These famed Letters to Young Poet in retrospect show Rilke mirroring Rodin to some extent, crystallizing insights gleaned from their talks, and then passing pearls of wisdom on to a young Kappus, who was then 19 and Rilke 27.

After a period of silence following the 1906 firing, Rilke and Rodin rekindled in August of 1908. Rilke was now living with Isadora Duncan and other artists in an abandoned convent in Paris, which Henri Matisse had converted into a school and commune. Rodin met Rilke there, spent hours catching up, buried the hatchet, and decided to move in the following month. After the sculptor’s death, the building became Paris’s Rodin Museum.

The book depicts both men’s messy marriages and complex relationships with women. Their success, like most men of their times, was on the backs of women whose exploitation cultural norms sanctioned.

So far the book reviews havemostly been rave, though Francesca Wade at the Financial Times chided Corbett for occasional breathy writing that grates. Yes, she sometimes waxes poetic after several clear sharp descriptive sentences. And while it might strike as jarring to change voice, some of us like it when a florid sentence breaks the flow. How could an occasional poetic flourish be a crime in a book about Rilke?

Rilke loved metaphor unabashedly — even though some of his verses risk feeling cheesy by today’s standards. The book’s title You Must Change Your Life is a case in point. It’s the last lines in Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo.” But, deftly, Corbett makes you wait for it. She doesn’t discuss this poem until page 202. By then, it’s clear how Rodin taught Rilke to see sculpture. It’s clear how meticulously scrutinizing every part of the sculpted body became a metaphor for scrutinizing every part of our life, in the spirit of that adage of Socrates that the unexamined life is not worth living.

It’s hard to resist connecting Rilke’s poem about a headless torso to the ones that abounded on the sculptor’s estate. Rodin had a penchant for antiquities. A picture from the archives of Paris’s Rodin Museum shows Rilke, Rodin, Rodin’s wife, and dogs with some headless torsos behind them.

We will never know whether Rilke had Rodin in mind when he wrote. But it’s undeniable a lot went well when he met Rodin. And while an artist taking on a protégé is not unique, that Rodin and Rilke bonded despite differing languages, ages, and artistic disciplines is noteworthy. As Rilke wrote to Kappus, “in the deepest and most important matters, we are unspeakably alone; and many things must happen, many things must go right, a whole constellation of events must be fulfilled, for one human being to successfully advise or help another. ”

It mig

ht seem strange to open this review with Auguste Rodin‘s signature on his sculpture “The Thinker.” But, the graceful curl of each letter amidst rough textures hints at Rodin’s lavish relationship with language. And it was contagious. A surprising new book reveals how Rodin’s way with words inspired Rainer Maria Rilke as a young poet.

Who knew that Rodin in his 60s met, inspired, and shaped Rilke in his 20s? Nowadays, it would be temping to call Rodin a mentor. The poet and the sculptor actually lived and worked together, spent hours conversing, and forged a special bond. Up until now, this connection was a mere footnote. At long last, Rachel Corbett, who edits Modern Painters, wrote the book this story deserves.

A riveting narrative unfolds in You Must Change Your Life: The Story of Rainer Maria Rilke and Auguste Rodin (W.W. Norton & Company) about bridging the generation gap. Corbett’s book is not only a case study in how a young poet learned from a renowned sculptor, but how Rodin found a way to connect with Rilke and a younger generation.

Corbett painstakingly researched how their lives intersected. Thirty-one pages of scholarly endnotes fastidiously anchor each assertion in a primary source. Nevertheless, the book moves along at a graceful fast clip; Corbett writes sharp prose that gets to the point.

Getting to the point wasn’t exactly Rilke’s forte. It may not be fair to expect that of any poet, especially one born in 1875 and swimming in the currents of the Symbolists. Rilke’s flowery — and daresay twee — verses do not jive with today’s tastes for cut-and-dry clarity, blasé irony, and Tweet-able brevity. But that’s precisely why Rilke is enjoying somewhat of a posthumous comeback. He offers what Twitter can’t.

But why did aging Rodin in his 60s capture Rilke’s imagination at the turn of the last century? It’s hard to see at first. What made Rodin radical then is no longer radical today. In his “Self-Portrait” (1890), Rodin grimaces amidst rough marks. The picture emblematizes how Rodin heralded raw and unpolished sculptures that were strikingly modern. It was a breath of fresh air since most of early-19th-century sculpture was smooth, neoclassical, and to be harshly honest, predictably dainty. Charles Baudelaire lamented this nadir in 1846 when he wrote his provocative essay “Why Sculpture is Boring.” Rodin went on to prove Baudelaire wrong. He showed how sculpture could be modern with distorted, coarse, rough textures. Rodin knocked the idealized body off its pedestal. And the modern sculptors that came after him saw no reason to put it back.

The pair first met outside Paris on Rodin’s country estate in September of 1902. Rilke, 26, took on a project as an art critic to write a German monograph on Auguste Rodin, at the time 61. Neither probably expected they would hit it off as much as they did. But long talks about art, and how to cultivate a work ethic bonded them together. Ten days into his initial stay on Rodin’s estate, Rilke wrote Rodin an affectionate letter confessing their dialogue’s intense effect. Rodin offered the young poet an open invitation to observe his studio for the next four months. During that time, Rilke not only gleaned insights for his monograph, but discovered how to be a better poet.

Three years later in September of 1905, Rilke took a job as Rodin’s assistant and lived with him full-time on his country estate. For the first time, Rodin’s correspondence was prompt and his files organized. Rilke relished more long talks with Rodin and the book is filled with examples of how Rodin stimulated the poet during this period of employment and intense dialogue.

One of the more amusing examples is how Rodin said good night to Rilke. Rather than “bonne nuit,” Rodinwould say, “bon courage,” roughly translated to “show courage” or “have good courage,” but this idiomatic expression is hard to translate. While an unusual way to say good night, Rodin was trying to telegraph to Rilke that he would need to be courageous as he prepared for the next day’s inevitable challenges.

Predictably, the honeymoon didn’t last forever. A row over a letter Rilke wrote to one of Rodin’s contacts without permission in April 1906 aroused Rodin’s suspicion, so he fired Rilke. But an indelible impression was nevertheless left on the poet.

An echo of Rodin can be heard in letters Rilke wrote to a young poet Franz Kappus. Their correspondence began in February 1903, just after Rilke first encountered Rodin in the fall of 1902, and it carried on for several years. These famed Letters to Young Poet in retrospect show Rilke mirroring Rodin to some extent, crystallizing insights gleaned from their talks, and then passing pearls of wisdom on to a young Kappus, who was then 19 and Rilke 27.

After a period of silence following the 1906 firing, Rilke and Rodin rekindled in August of 1908. Rilke was now living with Isadora Duncan and other artists in an abandoned convent in Paris, which Henri Matisse had converted into a school and commune. Rodin met Rilke there, spent hours catching up, buried the hatchet, and decided to move in the following month. After the sculptor’s death, the building became Paris’s Rodin Museum.

The book depicts both men’s messy marriages and complex relationships with women. Their success, like most men of their times, was on the backs of women whose exploitation cultural norms sanctioned.

So far the book reviews havemostly been rave, though Francesca Wade at the Financial Times chided Corbett for occasional breathy writing that grates. Yes, she sometimes waxes poetic after several clear sharp descriptive sentences. And while it might strike as jarring to change voice, some of us like it when a florid sentence breaks the flow. How could an occasional poetic flourish be a crime in a book about Rilke?

Rilke loved metaphor unabashedly — even though some of his verses risk feeling cheesy by today’s standards. The book’s title You Must Change Your Life is a case in point. It’s the last lines in Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo.” But, deftly, Corbett makes you wait for it. She doesn’t discuss this poem until page 202. By then, it’s clear how Rodin taught Rilke to see sculpture. It’s clear how meticulously scrutinizing every part of the sculpted body became a metaphor for scrutinizing every part of our life, in the spirit of that adage of Socrates that the unexamined life is not worth living.

It’s hard to resist connecting Rilke’s poem about a headless torso to the ones that abounded on the sculptor’s estate. Rodin had a penchant for antiquities. A picture from the archives of Paris’s Rodin Museum shows Rilke, Rodin, Rodin’s wife, and dogs with some headless torsos behind them.

We will never know whether Rilke had Rodin in mind when he wrote. But it’s undeniable a lot went well when he met Rodin. And while an artist taking on a protégé is not unique, that Rodin and Rilke bonded despite differing languages, ages, and artistic disciplines is noteworthy. As Rilke wrote to Kappus, “in the deepest and most important matters, we are unspeakably alone; and many things must happen, many things must go right, a whole constellation of events must be fulfilled, for one human being to successfully advise or help another. ”

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

If you'd like an alternative to randomly dating girls and trying to find out the right thing to do...

ReplyDeleteIf you would prefer to have women pick YOU, instead of spending your nights prowling around in filthy bars and night clubs...

Then I encourage you to play this eye-opening video to uncover a strong secret that can literally get you your very own harem of attractive women just 24 hours from now:

FACEBOOK SEDUCTION SYSTEM!!!