The Fateful Attraction of Jasper Johns and Edvard Munch

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

The Fateful Attraction of Jasper Johns and Edvard Munch

Sometimes an exhibition, propelled by its clarity of purpose and emotional force, will lead you to a point that feels genuinely cathartic. And sometimes an exhibition will hit that mark and then shift into overdrive.

RICHMOND, VA — Sometimes an exhibition, propelled by its clarity of purpose and emotional force, will lead you to a point that feels genuinely cathartic. And sometimes an exhibition will hit that mark and then shift into overdrive.

Jasper Johns and Edvard Munch: Love, Loss, and the Cycle of Life at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond brings together more than 60 works from each artist, 128 in all, in an exploration of affinity and influence that goes to the heart of a singular American artist’s lineage and identity.

And it does so by straddling the unbridgeable gulf that seems to exist between the intentions and accomplishments of the two artists. Given Johns’ antipathy to Expressionism in general (and Abstract Expressionism in particular, which he memorably skewered in such works as “Painting with Two Balls,” 1960), it is hard to imagine him even liking Munch’s frequently lurid Symbolism all that much — even if he did borrow the title for a set of three paintings, “Between the Clock and the Bed” (1981-83), from Munch’s elegiac “Self-Portrait between the Clock and the Bed” (1940-43).

Still, it is important to assess this appropriation against Johns’ habitual slipperiness of intent and aversion to definitive conclusions. The “Clock and the Bed” paintings are the last works in his decade-long “Crosshatch” series, and their significance within his oeuvre might lead you to suspect that their connection to the Munch self-portrait lies well beneath the surface.

It is a connection, however, that is fraught with ambiguity. In “Self-Portrait between the Clock and the Bed,” Munch portrays himself standing at attention, facing the viewer with his hands dangling helplessly at his sides, poised between time (the clock) and death (the bed). It is a memento mori etched in twilight, an act of desperation, if not despair, from an artist coming to terms with the inevitability of his own oblivion.

Johns, with his characteristic reticence and disinclination toward emotional display, could have meant his abstracted versions to be parodies as much as homages. In fact, the satirical interpretation would seem to hold more sway. By deconstructing this signal painting from Munch’s late period, he could be targeting Expressionism at its source, sending it up in both its representational and non-objective forms.

But this would be an inaccurate or, at the very least, insufficient reading, if we are persuaded by the terms set out by John B. Ravenal, who conceived and organized the exhibition. (Ravenal, who formerly served as the Sydney and Frances Lewis Family Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, is now the Executive Director of the DeCordova Sculpture Park and Museum in Lincoln, Massachusetts.) The relationship between Johns and Munch, he contends, is sweeping and profound.

As he states in the show’s introductory wall text, “Johns first encountered the art of Edvard Munch at age twenty when he visited the 1950 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. But it was some twenty-five to thirty years later that Johns began to mine Munch’s work for inspiration, studying his innovative techniques and signature themes of love, loss, sex, and death. These aspects of Munch’s approach may have gained increasing resonance for Johns as he passed the milestone age of fifty and as the AIDS crisis worsened.”

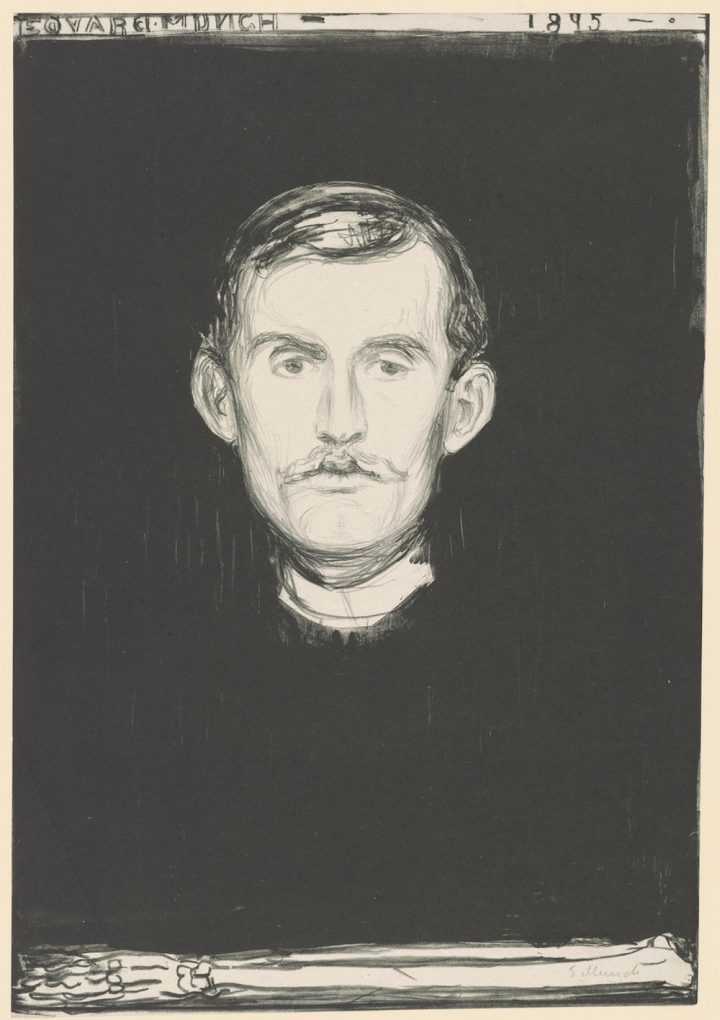

That Johns returned to an early and presumably formative experience with Munch’s work after he had reached middle age is in keeping with the cyclical themes of the exhibition, but Ravenal doesn’t ask us to take the interrelationship on faith. Instead, he builds his case step by step, offering such evidence as Johns’ use of painted wood grain in his “Savarin” prints (paralleling the faux wood grain in Munch’s 1895 lithograph of “The Scream”), along with a skeletal arm or arm-print inside a predella-like strip in several of the images, which match a corresponding arm in a lithographic self-portrait by Munch, also from 1895.

Other similarities abound: the use of pictorial framing devices, such as the illusionistic, sperm-filled border of Munch’s “Madonna” lithographs (1895/1902); the forks, knives, and spoons that both artists employ as signifiers of consumption and mortality; the pairing, on adjacent walls, of Johns’ “Dancers on a Plane” (1980) and Munch’s “The Dance of Life” (1925), with their comparable value range and coloration (dark purples and greens enlivened by white, red, and ocher). There are also the relentless printmaking experiments in which the artists explore variations and paraphrases of the motifs inhabiting their paintings.

The cumulative effect of these correspondences ratchets up the intellectual fascination of the two bodies of work even as the dissimilarities in style and outlook between hot Munch and cool Johns make for an oddly fractious, even emotionally alienating viewing experience.

That disparity comes to an end, however, and the exhibition reaches a climax, in the large room holding Munch’s “Self-Portrait between the Clock and the Bed” and Johns’ “Between the Clock and the Bed” series, complete with an iron-post bed covered by Munch’s actual summer-weight bedspread, which Ravenal had personally dug out of the archives at the Munch Museet.

The inclusion of the bed, which looks as if it were left behind from a piece of performance art, intrudes on the two-dimensional works in a way that spikes their contemporaneity while underscoring their relationship to reality, with Munch once removed and Johns twice removed; Munch’s painterly treatment of his immediate surroundings is fevered and unfiltered, while Johns’ abstracted interpretations of Munch’s imagery are sumptuous and heady.

Johns’ “Crosshatch” paintings may be the most resolutely abstract work of his career (and such prize canvases as “Cicada,” 1979, and “Corpse and Mirror II,” 1974-75, are included in the show), but after ten years of working exclusively in that mode (that is, in paintings — prints and drawings were a different case), the abstractness of the “Clock and Bed” pictures comes apart in a way that opens the door to the artist’s richly varied and sometimes maddeningly elusive middle and late works.

Each of the paintings is composed of three abutting vertical canvases, with a subset of smaller crosshatches in the lower right panel suggesting the bed, while the light-colored vertical column in the middle represents Munch, and the darker one on the left assumes the general shape of the grandfather clock.

Here, Johns’ sometimes coy interplay with Munch goes all in, and the emotional consequences are overpowering. As in his early adaptations of flags, targets, and maps, Johns is using a readymade as a vehicle to convey hidden meanings, but the readymade in this instance is Munch’s emotionally freighted persona.

It can be conjectured that, when he saw Munch’s retrospective in 1950, it touched a nerve that he would have the capacity to revisit only as a seasoned artist in middle age. And if, through crosshatching, Johns has distanced himself from Munch in order to tap into a secondary set of meanings, the absence of irony in this set of works delivers an emotional sucker punch that simply floors you.

In hindsight, it might seem premature for a man in his early 50s to be contemplating death, especially since he is now a very productive 86-year-old, but, as Ravenal mentions in his wall text, this was a time when the death toll from AIDS began to climb precipitously, and the gay community catapulted in a few short years from confusion and dread to mourning and outrage. Always reserved, Johns turns Munch’s end-time painting to his own purposes, waxing philosophical rather than political, boring into the meanings that the life cycle holds for him.

And he does so in a fundamentally different way than he did with a painting like “Cicada,” which suggests its connection to death, rebirth, and renewal exclusively through its title (though a drawing version in watercolor, graphite pencil, and crayon, also in the show, includes a predella of notebook sketches depicting cicadas, phallic symbols, and a skull and crossbones, among other images and jottings).

With his three paintings based on Munch’s “Self-Portrait between the Clock and the Bed,” he takes a step away from both reference and literalism, into a complexly allusive realm where the patch of lighter color in the middle panel is meant to convey, in the artist’s words (documented on a wall label), “an existence between two existences.”

Typically ambiguous, the statement could refer to Munch’s existence between the existences of the clock and the bed, or the three states of existence spanning natality (the subject of Munch’s “Madonna” painting and prints), life, and death. Of the three canvases in Johns’ series, two are in encaustic, one of which is mostly black, white, and gray, the shades of mourning, while the dominant colors of the other are purple, orange, and green, which feel springlike by comparison.

The third painting is in oil and repeats the secondary color scheme of the purple, orange, and green encaustic, but in the right panel, above the bed, Johns has printed an off-kilter, black-and-white image from the same silkscreen he used for a three-part crosshatch print called “Usuyuki” (1981), which is in turn based on the transcendently beautiful painting of the same name from 1977-78. (Ravenal’s catalogue essay explains that the title “refers to both the Japanese word for falling snow and a Kabuki play about the melancholy relationship between an aging man and a beautiful young geisha he desires but can no longer possess.”)

As my Hyperallergic Weekend colleague John Yau, in his book-length study, A Thing Among Things: The Art of Jasper Johns (D.A.P, 2008), found by closely inspecting “Flag” (1954-55) — where the words “Pipe Dream” are embedded in one of the white stripes — nuggets of meaning are often flecked onto Johns’ surfaces, especially when he is using encaustic, which entails dipping strips of newspaper into pigmented molten wax and applying them as if he were making a collage.

The original painting of “Usuyuki” is encaustic, but much of the information contained in its newspaper strips is obliterated by the swatches of paint. However, much more of the newspaper type is legible in the screenprint, and its reiteration in the oil version of “Between the Clock and the Bed” includes the word “Baby” as well as an obituary headline, repeated in an adjoining section, for John (Johnny Dio) Dioguardi, a New York mobster who was imprisoned with Henry Hill, of Goodfellas fame, in Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary in Pennsylvania, and died on January 12, 1979, at the age of 64.

Make what you will of the similarity between Johns’ surname and the gangster’s first name, or that Dioguardi translates as “Look at God,” the presence of an obituary headline and the word “Baby” inside of a picture-within-a-picture that is potentially redolent of unrequited love, might suggest a wrenching of the life cycle from its usual birth-death-rebirth narrative into a more cordoned-off emotional terrain of abandonment, lost hope, and loneliness.

Again, that’s conjecture, but the openness of these works, which ditch the formality and head games of prior “Crosshatch” paintings, allows you to latch onto them from any angle. And the shift of emotional magma beneath the surface seems to have had an eruptive impact on Johns, because from this point forward his work spills out in any number of unexpected directions.

Standing in front of the three “Clock and Bed” paintings, Munch’s self-portrait, and a real bed, I felt that the exhibition couldn’t get any more spectacular — but then it did, and then it did again.

After sending you down a corridor filled with every variety of “Savarin” prints, the show opens up to a series of rooms featuring one Johns masterwork after another. The convulsive “In the Studio” (1982) — with its depiction of two crosshatch paintings (with one of them melted and dripping), along with a tall, narrow, vertical strip of wood leaning into the viewer’s space from the bottom of the canvas, and a red-yellow-and-blue wax cast of a hand and forearm (beside a faux-drawing of the same) — inevitably brings to mind the disembodied arms along the predellas of the “Savarin” prints as well as Munch’s lithographic self-portrait, creating new chains of meaning among Johns’ interlocking works of the mid- to late-1980s.

Nearby, the staggering “Perilous Night” (1982) combines wax arms, crosshatching, and wood grain, to name just a few of the motifs highlighted in the show, while half of the composition is taken up by a darkly oblique reference to Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece(c.1512–1516). Munch’s “Inheritance” (1897-99) hangs on an adjacent wall, in which a grieving mother and a syphilitic baby are offset by a green background that matches the central green rectangular field in “Perilous Night” (and which Ravenal explained was the color of billiard table felt, and thereby considered degenerate in Munch’s day). Rounding off the room is “Untitled” (1984), one of Johns’ “Bathtub” paintings, which includes, among other motifs, a skull and crossbones alongside wood grain panels, optical illusions, and another oblique reference to Grünewald.

The final room of the exhibition is dedicated to Johns’ encaustic polyptych “The Seasons” (1985-86), a blatantly autobiographical work that takes the life cycle literally, with a black semicircle in each panel indicating, via the direction of the artist’s arm-print, how far he has advanced along his lifeline. The surfaces are chockablock with Johns symbology, including crosshatching, wood grain, optical illusions, and Grünewald, which are all encroached upon by the artist’s shadow, traced from life and posed in a stance similar to Munch’s in “Self-Portrait between the Clock and the Bed.”

The paintings, which take up an entire wall, are placed in the context of shadow-dominated works by Munch, including “Starry Night II” (1922-24), “Self-Portrait in Moonlight” (1904-6) and “Self-Portrait in Hell” (1903). The Munchs may get a bit ponderous, but the beauty and lightness of “The Seasons” dispel any whiffs of fatalism or portentousness. The sense you get, upon reaching this room, is that whatever Johns carried away with him from his initial encounter with Munch — alienation, isolation, and existential horror are possible guesses — has been, if not purged, then liberated from the confines of single motifs, generating a newfound combinatory idiom that could take him anywhere and everywhere.

When these paintings first appeared, 30 years after the skyrocketing success of “Flag” and other early works, they seemed to have a valedictory air about them. Now, 30 years later, they have become yet another clearing in the field of an artist who has never ceased to change and grow. His absorption of Munch, along with Grünewald, Picasso, Leonardo and other masters, has been in the service of his own transformational psyche, not as a means to prettify or legitimize his works with an art historical pedigree. Each creative stage informs the next, which in turn reevaluates what came before. With Johns, even as you plumb the implications of a particular motif or detail, it’s always the long view that matters.

Jasper Johns and Edvard Munch: Love, Loss, and the Cycle of Life continues at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (200 N. Boulevard, Richmond, Virginia) through February 20, 2017.

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Comments

Post a Comment