Max Beckmann- Nazis,& New York,

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Nazis, New York, and Max Beckmann

What New York gave Beckmann was not superficial subject matter, but inspiration in the form of energy.

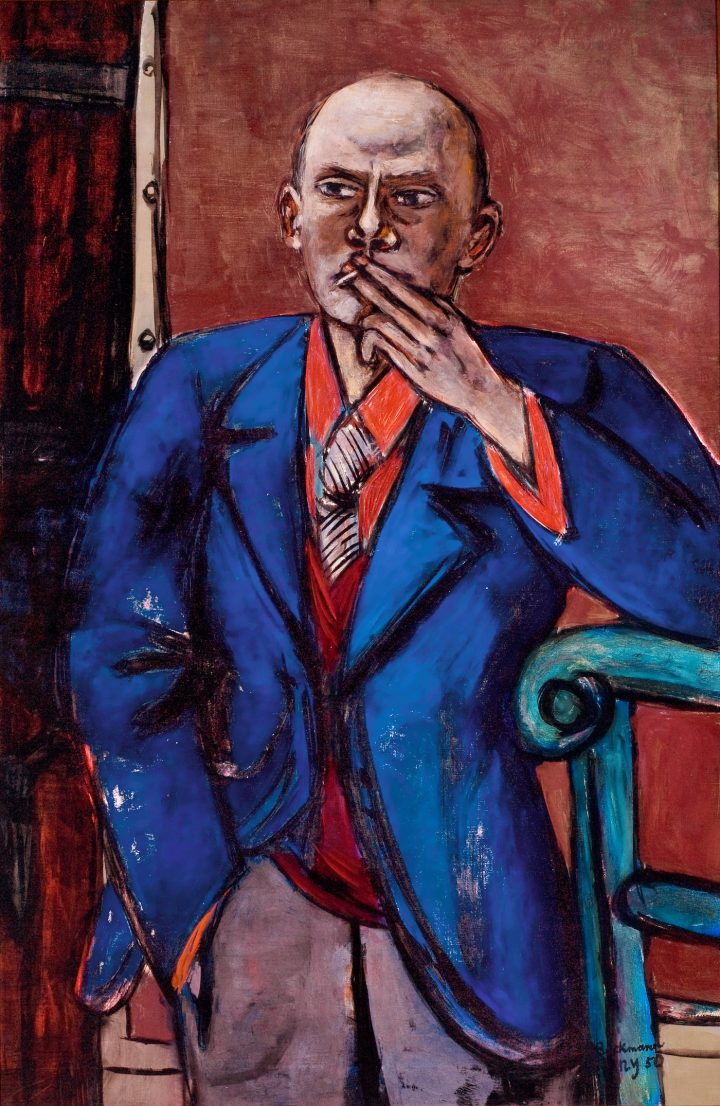

Max Beckmann in New York, currently on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, opens with a story. “Self-Portrait in Blue Jacket” (1950), which greets you at the entrance, was included in an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum the year it was painted. Beckmann, who was 66 years old at the time, and living in New York, set out to see his painting hanging in the museum. He never made it; he suffered a fatal heart attack at the corner of 69th Street and Central Park West.

This story — a poignant message about painting up until the day you die, or just a poetic tragedy, depending on your outlook — was the original inspiration for the curator, Sabine Rewald. The exhibition investigates Beckmann’s relationship to the city in two ways (Rewald calls the exhibition title a “double-entendre”). It includes paintings Beckmann made during his New York years, as well as paintings that are part of public and private New York collections.

Luckily, this premise — an odd combination that functions as an a priori curatorial method — resulted in a fine, manageably sized show of thirty-nine paintings spanning a range of years (the 1920s through 1950). Without a lot of excess, it gives us a sense of how radically Beckmann’s painterly style evolved over the decades, and how he worked.

Stories are told throughout the show – about Beckmann’s biography and the fascinating provenance of many pieces. It is tempting to hinge Beckmann’s painting on this compelling art historical armature, but to do that would miss the mark. Beckmann famously resisted telling the stories of his paintings. His work is relentless in its evasion of any clear, easily digestible narrative.

The exhibition literature suggests, almost wistfully, that Beckmann doesn’t fall neatly into the show’s theme: he never really painted New York City; instead, he showed us the interiors of his favorite watering holes — the bars of the St. Regis and the Plaza Hotel (he was evidently not socializing with the Abstract Expressionists at the Cedar Bar). And, although he took daily walks around this island of Manhattan — Central Park, Chinatown, and the Upper West Side — he never made a New York cityscape.

Instead, Beckmann painted from memory, imagination and a personal iconography. He painted archetypes rescued and blended from both universal and iconoclastic mythologies — mothers and kings, torturers, bound and flayed captives, fish and birds, hybrid creatures, himself, his wife, friends and strangers, who gather with a spectrum of props: costumes, masks, stringed and brass instruments, formal dress, and most ubiquitously, a lit cigarette in hand.

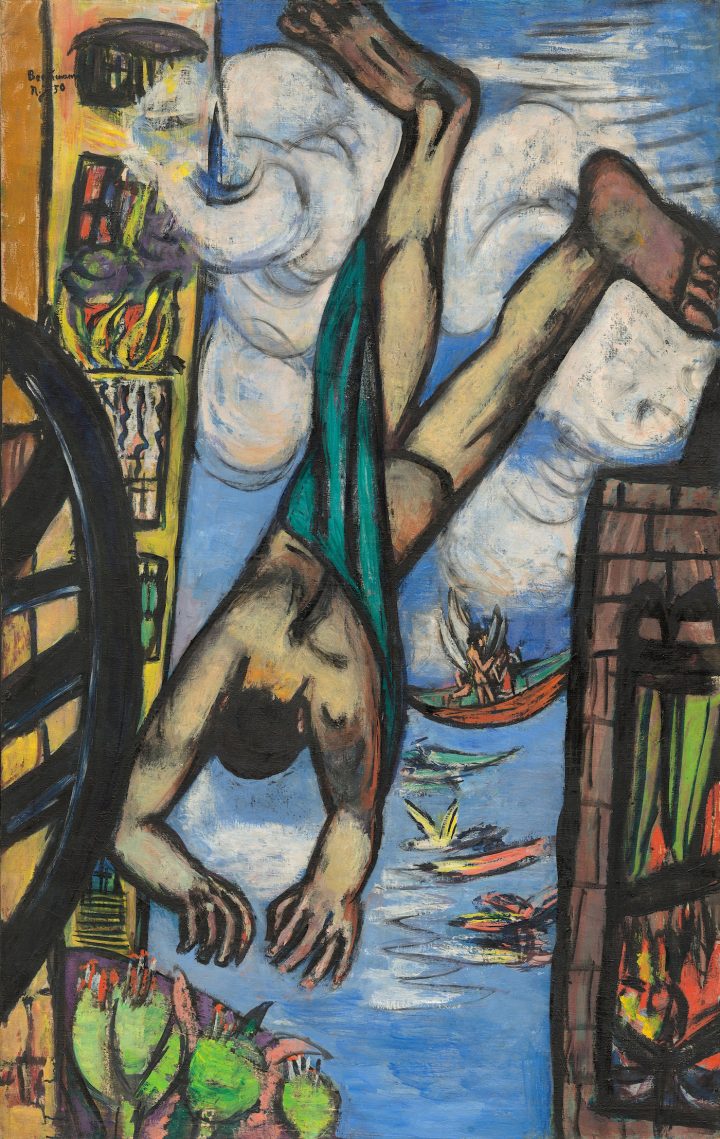

To my mind, the revelation of the exhibition was the fluidity of the 1949-50 paintings, and how fiercely productive Beckmann was during his sixteen months in New York. Beckmann was working at the height of his powers, making forty paintings, including the magnificent “Self-Portrait in Blue Jacket,” “Falling Man,” “Beginning,” “The Town (City Night),” and “Carnival Mask, Green, Violet, and Pink (Columbine),” all completed in 1950. I wished that the late work had been installed together so that this period could be seen as a single statement. Like many exhibitions today, the installation is organized partly by subject matter, and partly by chronology. Here, we have rooms of self-portraits, landscapes, “Muses,” and “Hell and Other Places.”

Clearly, what New York gave Beckmann was not superficial subject matter, but inspiration in the form of energy. His painterly style, developed and refined out of four decades of working, became bolder, his figures and forms more monumental, his use of black more prominent, his sense of space – compressed but never flattened – more self-assured.

Although Beckmann refused to explain the symbolism of repeated motifs like crowned figures, fish, ladders and brass instruments, he was clear about one issue. He did not believe in complete abstraction, completely flattened forms, or extreme stylization. Although he compressed space, and is said to have had a horror vacui of deep space (based on battlefield trauma of volunteering as a medical orderly during World War I), he insisted on an empathic identification with actual objects, and the depiction of space and air around them.

Beckmann said, “If the canvas is only filled with a two-dimensional conception of space, we shall have applied art, or ornament. To transform three into two dimensions is for me an experience full of magic.” (Max Beckmann, “On My Painting,” lecture, first read in London, July 21, 1938.) In an earlier essay, he had written, “Quality [is] the feeling […] for the peach-colored sheen of skin, for the glint of a nail, for the sensual in art, which resides in the softness of flesh in the depth and gradation of space, not only on the surface but also in depth.” (Max Beckmann, “Thoughts on Timely and Untimely Art.” In Pan, March 14, 1912.)

Beckmann, in these statements, was defining and defending his aesthetic turf. Across several countries and decades, he resisted movements that propounded abstraction and pictorial flatness as the apex of painting. He lived in Germany, Amsterdam, and the United States, but he was not an expressionist or pioneer of abstraction like Franz Marc, Kandinsky, or Mondrian, or a New York School Abstract Expressionist. His work was shown in the 1923 exhibition in Mannheim, for which curator Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub coined the movement Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), but Beckmann was never an overt a societal chronicler as peers Otto Dix and George Grosz. His was not an easy position to occupy; he didn’t fit any established art historical narrative.

Beckmann was in some form of exile for most of his life. He had a nervous breakdown after his service in World War I and did not return to family life with his first wife and son. In the 1930s he was declared a degenerate artist by the Nazis, and was exiled to Amsterdam for a decade. He was never able to penetrate the French art world or the Paris market. He arrived in the United States in 1947, first teaching at Washington University in Saint Louis, Missouri, and then in New York, where he taught at the Brooklyn Museum Art School.

It may be inconvenient for art historians, but in his painting, Beckmann never gave us everything; he doesn’t allow us to penetrate meaning that way. It is not an accident that Beckmann loved costumes and guises. His painting is poly-referential, suggestive through form rather than content. Addressing his first class at Washington University in 1947 (an advanced painting class he took over from Philip Guston), Beckmann said:

Please do remember this maxim – the most important I can give you: If you want to reproduce an object, two elements are required: first, the identification with the object must be perfect; and secondly, it should contain, in addition, something quite different. This second element is difficult to explain. Almost as difficult as to discover one’s self.

His painting “Falling Man” is difficult to explain, which makes it tempting for an art historian to describe it as a foreshadowing of television news images we saw on 9/11. The painting has also been interpreted as an illustration of Beckmann’s spiritual interests. Like other artists of his generation, he was interested in Theosophy, the concept of the fourth dimension, and he studied Indian philosophy and the Vedas. And yes, Beckmann seemed to embrace the idea, as an artist, that he could be a seer and truth-teller. But “Falling Man” is magic by its own internal, impossible contradictions. The legs and feet are oversized, weighty, splayed, taking up a large piece of the upper part of the painting. Clouds are pressed up against the picture plane; they are thick, tangible paint, all about air and atmosphere, yet they are also light enough to pass though the figure and the tall building at the left.

Beckmann’s painting does not position itself on any one side of a polemical position. Rewald refers to “Bird’s Hell” (1938) as his clearest indictment of Nazism. While this is likely true — the painting is full of nightmarish, weird, perverse imaginings – it is still, determinedly, a message told in metaphor: formal and imagistic. Across his entire body of work, Beckmann matches perversity with tenderness, detachment with intimacy, angst and darkness with celebration and rich color.

He loved to paint women and figures with splayed legs – this vision goes all the way back to the 1906 painting “Death Scene,” made in response to the premature death of his mother. Curiously, a female nude squats at the bedside in grief. The squatting or splayed-leg pose is a leitmotif across his triptychs, and it is featured prominently in “Columbine.” But his depictions of his second wife, Quappi, are about wholeness. In a painting like “Quappi in Grey” (1948), her small, delicate features are held together in Beckmann’s hand, and with his line.

It is often said that Beckmann’s paintings look like stained glass, but his black outlining doesn’t facet forms as much as bind the whole composition, giving us a taste of wholeness, connection, and joy. He does this in his cityscape “San Francisco” (1950), where black lines, marking a trio of echoing curves delineating road, shoreline, and clouds, feel as playful as a children’s drawing. In “Mill in Eucalyptus Forest” (1950), Beckmann imagines a mill into the landscape around Mills College, which didn’t actually exist. It’s verbal/visual play. Somehow, his black lines mark the air around forms, their roundedness.

Ultimately, this is the stage that “Self-Portrait in Blue Jacket” sets. It is a portrait of interiority (the painter smoking a cigarette, gazing off to the side), but it reaches us through the depth of its color, the energy of the staccato lines on the knot of the tie, the abstract play of triangles and curves. Beckmann’s refusal to give us everything — to close his paintings down with explicit narrative — was about generosity. He invites us in.

Max Beckmann in New York continues at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1000 Fifth Avenue, Upper East Side, Manhattan) through February 20, 2017.

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Comments

Post a Comment