The Bird-Based Color System that Eventually Became Pantone

The Bird-Based Color System that Eventually Became Pantone

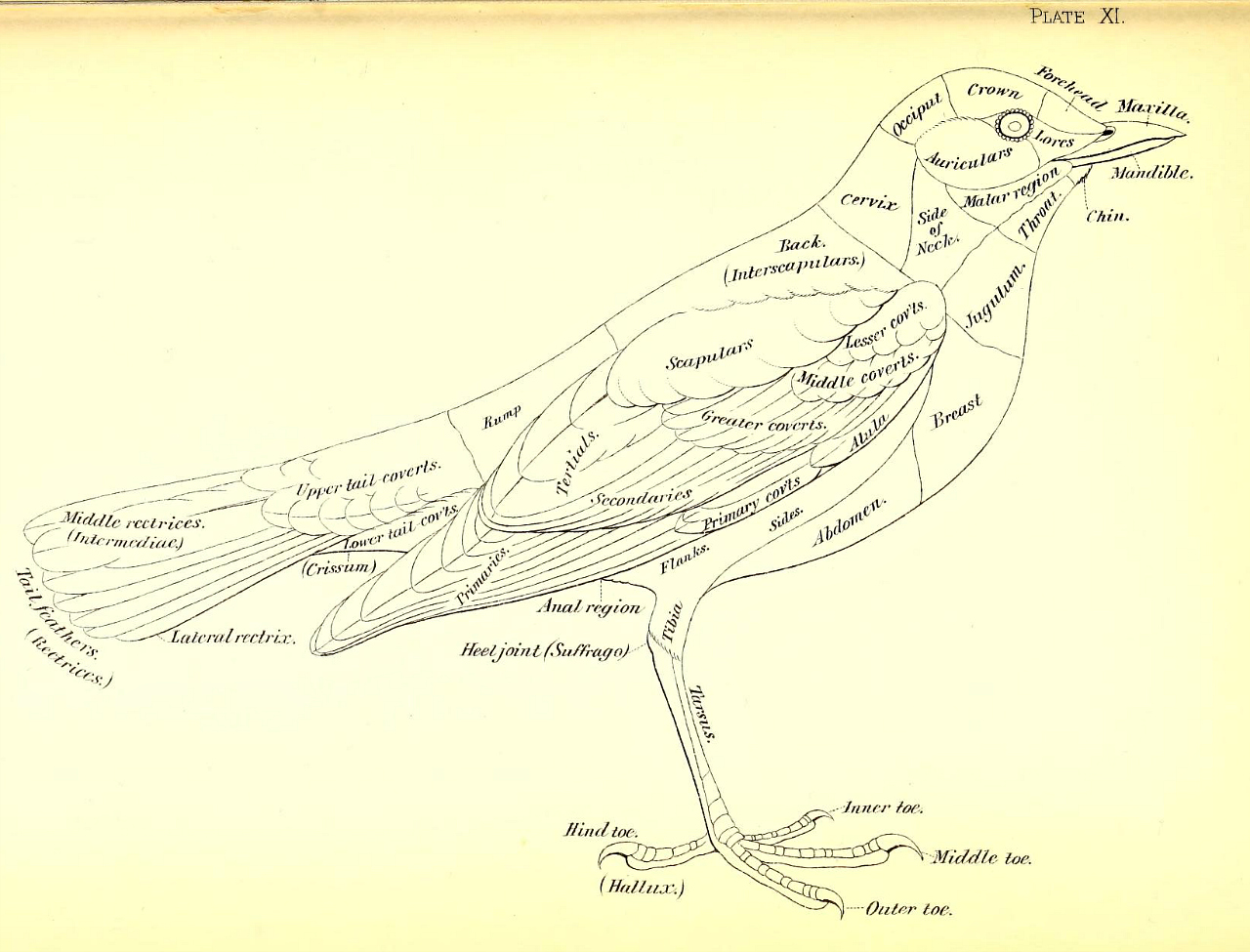

Bird diagram from Robert Ridgway’s ‘A nomenclature of colors for naturalists : and compendium of useful knowledge for ornithologists’ (1886) (via Smithsonian Libraries)

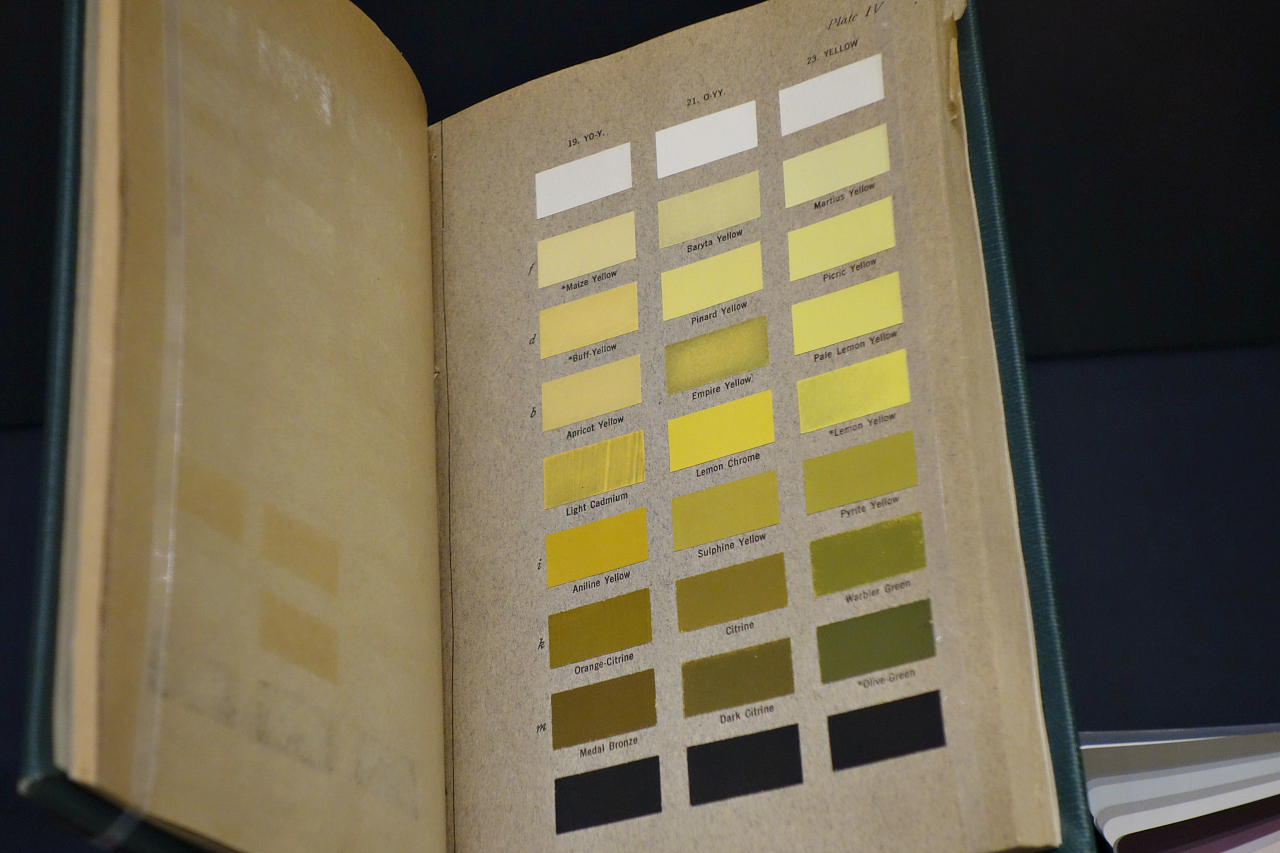

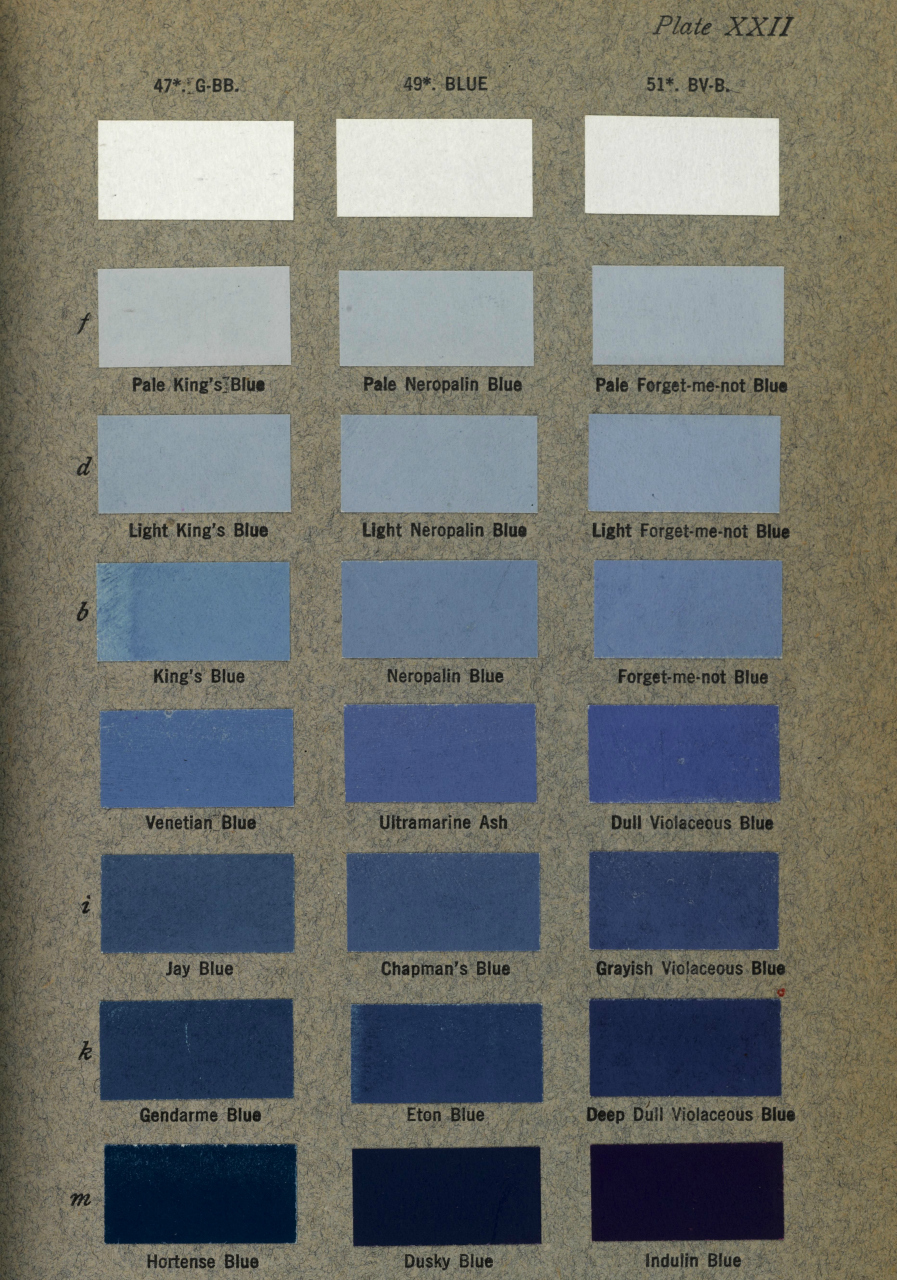

WASHINGTON, DC — An effort to describe the diversity of birds led to one of the first modern color systems. Published by Smithsonian ornithologist Robert Ridgway in 1886, A Nomenclature of Colors for Naturalists categorizes 186 colors alongside diagrams of birds. In 1912, Ridgway self-published an expanded version for a broader audience — Color Standards and Color Nomenclature — that included 1,115 colors. Some referenced birds, like “Warbler Green” and “Jay Blue,” while others corresponded to nature, as in “Bone Brown” and “Storm Gray.”

Colors in Robert Ridgway’s ‘Color Standards and Color Nomenclature’ (1912), including “Peacock Blue” (via Biodiversity Heritage Library/Missouri Botanical Garden) (click to enlarge)

Ridgway wrote in his 1912 preface that “the nomenclature of colors remains vague and, for practical purposes, meaningless, thereby seriously impeding progress in almost every branch of industry and research.” He railed against confusing trade names like “‘zulu,’ ‘serpent green,’ ‘baby blue,’ ‘new old rose,’ ‘London smoke,’ etc., and such nonsensical names as ‘ashes of roses’ and ‘elephant’s breath.'”

A copy of Ridgway’s 1912 book is on view in the Smithsonian Libraries’ Color in a New Light. Installed in two large display cases on the ground floor of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, the exhibition examines the point at which art, history, and science blend through color. Ridgway’s research is joined by the work of 19th-century painter Gerald Handerson Thayer, whose studies of animals disguising themselves influenced military camouflage; a discussion ofFiestaware, which was painted with orange-red uranium oxide glaze and thus became unintentionally radioactive; and the history of Tyrian Purple pigment, made by mashing up snails.

Color systems date back centuries, at least to Richard Waller’s 1686 Tabula colorum physiologica. Yet bird-watching hones a sharp eye for color differentiation, so Ridgway had an edge — as well as a drive for perfection enabled by 19th-century synthetic dye advancements. This new color technology wasn’t without its dangers. One sample in Ridgway’s book is labeled “Scheele’s Green,” a reference to Wilhelm Scheele’s toxic mix of arsenic and copper.

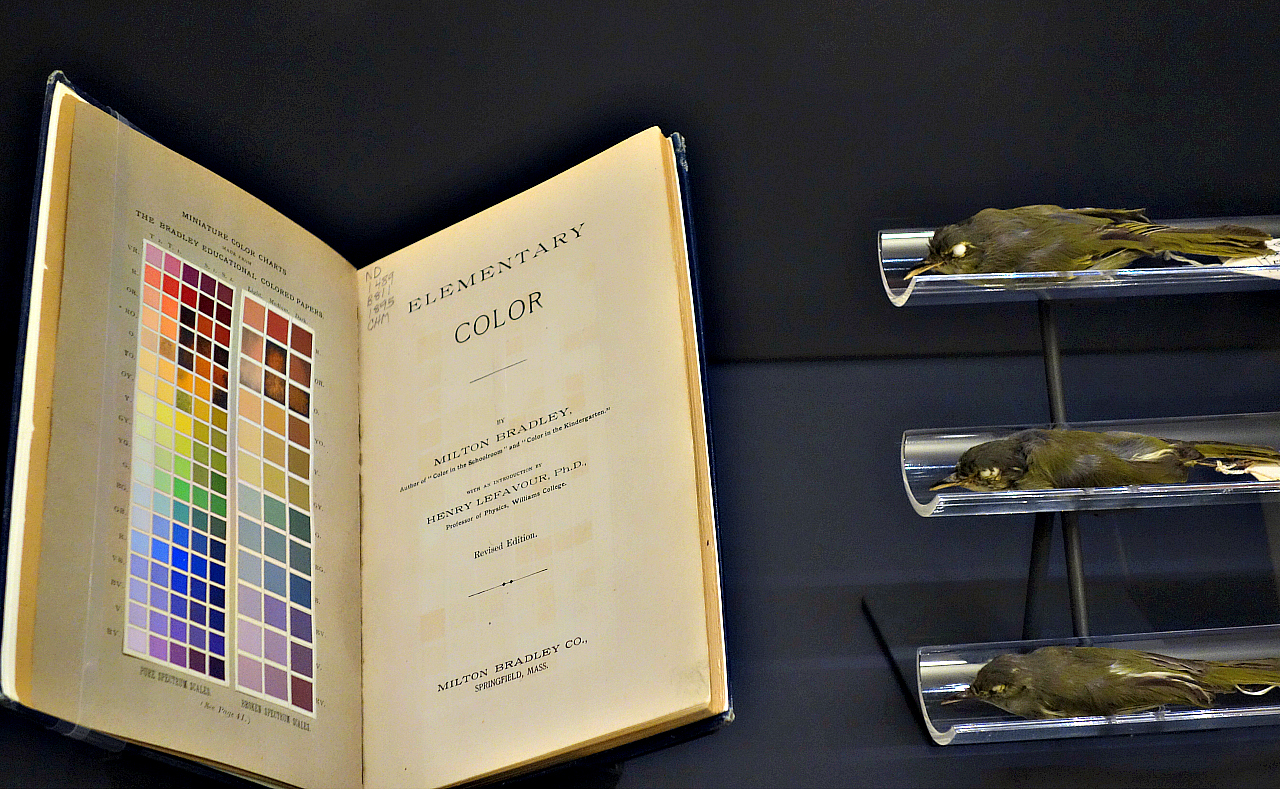

Milton Bradley’s ‘Elementary Color’ (1895) with three leaf warblers (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Milton Bradley, ‘Elementary Color’ (Springfield, Massachusetts, 1895), Milton Bradley Co, Gift of Binney & Smith, Inc, makers of Crayola Crayons (courtesy Smithsonian Libraries) (click to enlarge)

Ridgway’s scientific work was inspired by Milton Bradley, who, along with selling board games, was a proponent of color education. He published Elementary Color in 1895 and manufactured a color wheel that, when spun, visually mixed different hues. Daniel Lewis, author of a 2012 biography of Ridgway, wrote in an article for Smithsonian magazine that the ornithologist paid tribute to Bradley in his color system with “Bradley’s Blue” and “Bradley’s Violet.” Lewis added that Ridgway’s “book evolved into the Pantone color chart,” the first edition of which was printed in 1963.

Nevertheless, Ridgway’s colors were not widely adopted as a system. In a 1985 article published by the Beta Beta Beta Biological Society, Elisabeth B. Davis explains, at least in part, why: “Ridgway described his procedures carefully, Color Standards lacks precise descriptions of how to reproduce the colors. In addition to this problem, Ridgway chose some pigments that were not as permanent as he had hoped, but were affected by humidity, abrasion, and hue shift.”

The whole 1886 book is available to flip through online, thanks to the Smithsonian Libraries, and the 1912 expanded edition is accessible through Columbia University Libraries. At the Smithsonian Libraries, the institution’s copy of Color in a New Lightis installed alongside three stuffed leaf warblers from the Philippines, so you can compare the synthetic sample of “warbler green” to its inspiration in nature.

Three stuffed Philippine leaf warblers (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Robert Ridgway, ‘Color Standards and Color Nomenclature’ (1912), with “warbler green” third from the bottom on the right (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Colors in Robert Ridgway’s ‘Color Standars and Color Nomenclature’ (1912), including “Jay Blue” (via Biodiversity Heritage Library/Missouri Botanical Garden)

Feather diagrams from Robert Ridgway’s ‘A nomenclature of colors for naturalists : and compendium of useful knowledge for ornithologists’ (1886) (via Smithsonian Libraries)

Robert Ridgway, ‘Color Standards and Color Nomenclature’ (1912) (courtesy Smithsonian Libraries)

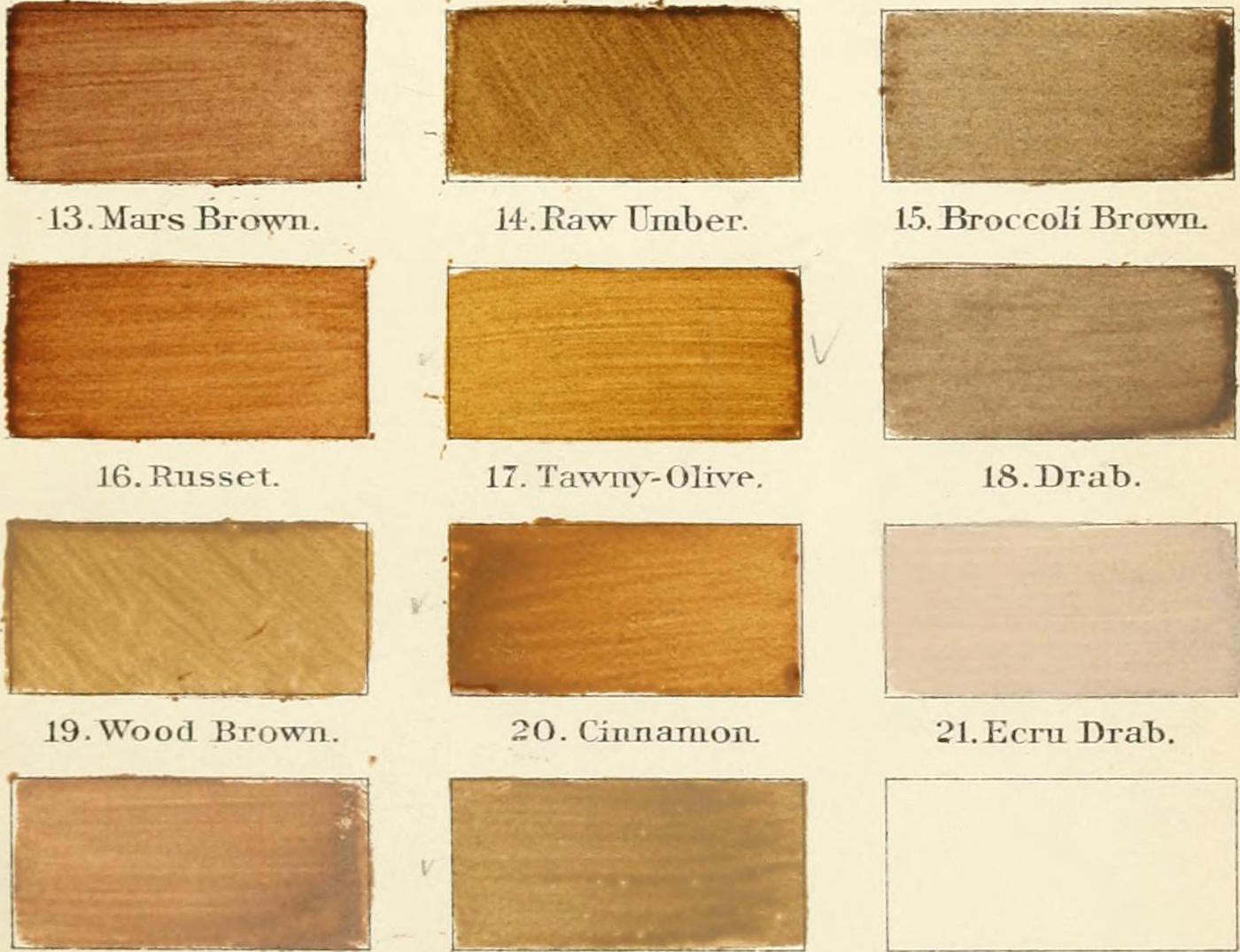

Colors from Robert Ridgway’s ‘A Nomenclature of Colors for Naturalists : And Compendium of Useful Knowledge for Ornithologists’ (1886) (via Boston Public Library/Wikimedia)

Colors from Robert Ridgway’s ‘A Nomenclature of Colors for Naturalists : And Compendium of Useful Knowledge for Ornithologists’ (1886) (via Boston Public Library/Wikimedia)

Colors from Robert Ridgway’s ‘A Nomenclature of Colors for Naturalists : And Compendium of Useful Knowledge for Ornithologists’ (1886) (via Boston Public Library/Wikimedia)

Installation view of ‘Color in a New Light’ at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (photo by the author for Hyperallergic) (click to enlarge)

The Smithsonian Libraries’ Color in a New Light continues at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (10th & Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, DC) through March 2017.

Comments

Post a Comment