The Leaders of Art Nouveau

If you’ve been to Paris or seen it in photos, you’ll recognize the swirling, plant-like gates, with their distinctive lettering, that serve as entryways to the city’s subway system, or metro, as it’s known there. Of the many terms for Art Nouveau in France, Style Metro remains one of the most persistent, thanks to Hector Guimard’s enduring design for the entrances. Unveiled during the Paris World’s Fair in 1900, the design would become a symbol of the Art Nouveau movement.

But it had begun years earlier. From the 1880s until World War I, artworks, design objects, and architecture in Western Europe and the United States sprouted with sinuous, unruly lines. Taking cues from Rococo curves, Celtic graphic motifs, Japanese masters Andō Hiroshige and Katsushika Hokusai, and William Blake’s Songs of Innocence(1789), Art Nouveau artists took the plant forms they saw in nature and then flattened and abstracted them into elegant, organic motifs.

The Movement’s Origins

The term Art Nouveau first appeared in the Belgian art journal L’Art Moderne in 1884 to describe the work of Les Vingt, a society of 20 progressive artists that included James Ensor. These painters responded to leading theories by French architect Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc and British critic John Ruskin, who advocated for the unity of all arts. In December 1895, the German-born art dealer Siegfried Bing opened a gallery in Paris named “Maison l’Art Nouveau.” Branching out from the Japanese ceramics and ukiyo-e prints for which he had become known, Bing promoted this “new art” in the gallery, selling a selection of furniture, fabrics, wallpaper, and objets d’art.

Encouraging the organic forms and patterns of Art Nouveau to flow from one object to another, the movement’s theorists championed a greater coordination of art and design. A continuation of democratic ideas from Britain’s Arts and Crafts movement, this impulse was as political as it was aesthetic. The movement’s philosophical father, the English designer and businessman William Morris, defined its main goals: “To give people pleasure in the things they must perforce use, that is one great office of decoration; to give people pleasure in the things they must perforce make, that is the other use of it.” Morris disdained the working conditions bred by the industrial revolution and abhorred the low-quality bric-a-brac created by factories and amassed in homes of the era.

He insisted that functional design be incorporated into the objects of everyday life, and his mix of aesthetics and ethics rejected the heavy ornamental qualities of the 19th century, specifically the cumbersome, almost suffocating excesses of the Victorian period. His ideas manifested as many distinct national flavors. In Scotland, there was the rectilinear Glasgow Style; in Italy, Arte Nuova or Stile Liberty, after the London firm Liberty & Co.; Style nouille (“noodle”) or coup de fouet (“whiplash”) in Belgium; Jugendstil (“young style”) in Germany and Austria; Tiffany Style in the United States; and in France, Style Metro, fin-de-siècle, and Belle Époque. For some, Art Nouveau was the last unified style; for others, it was not one style, but many. As with all art movements up until the late 20th century, it was dominated by men.

The Leaders of Art Nouveau

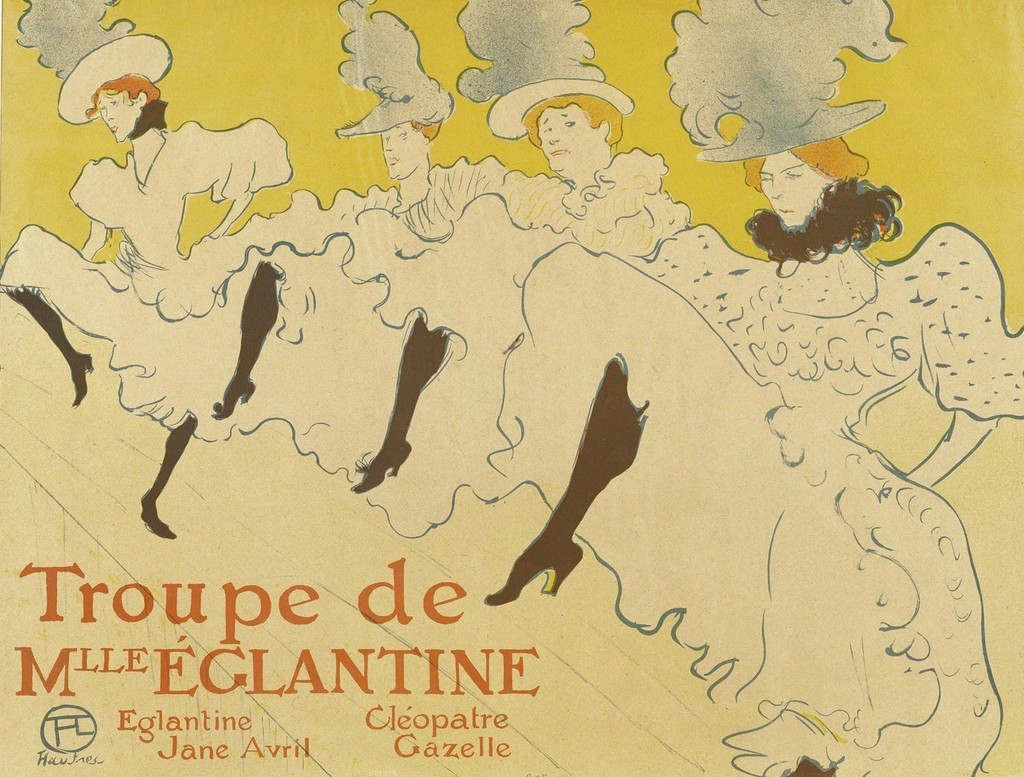

Perhaps the person who best expressed Art Nouveau’s steep historical arc, like a flame that burned brightly but briefly, was the young Englishman Aubrey Vincent Beardsley, whose perverse sensibilities made him the most controversial figure of Art Nouveau. Finding inspiration in the truculent manner of American expat James Abbott McNeill Whistler and in Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s Japoniste posters, Beardsley began his formal artistic career at just 19 years old. The celebrated Pre-Raphaelite painter Sir Edward Burne-Jones would come to shower praise on the untrained Beardsley’s drawings when he saw them in 1891.

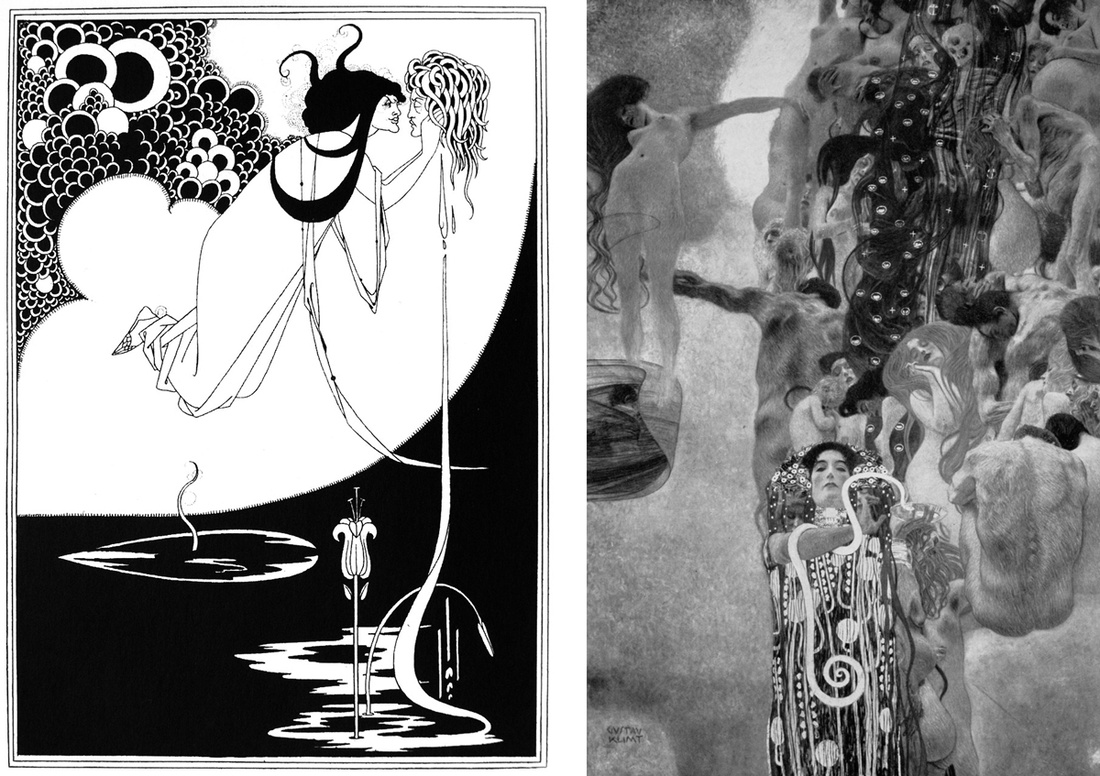

Beardsley’s India ink illustrations for Oscar Wilde’s play Salomé established many essential Art Nouveau ideals. Their shadowy imagery, flat decorative patterns, stark contrast, and controlled but swooping lines quickly earned the artist international recognition. Depicting the biblical story of Herod beheading St. John the Baptist at Salomé’s request, the drawing for “J’ai baisé ta bouche, Iokanaan” drips with erotic imagery: folds of fabric, streams of blood, and tendrils of hair. At lower right, a flower evocatively blooms in the darkness, while a black passage at upper left seems to reverberate with the dark thoughts of a scowling Salomé. Thanks to his formal talents—not to mention his propensity for erotic and sometimes pornographic subject matter—Beardsley became a touchstone for some of Art Nouveau’s most recognizable artists, despite his early death from tuberculosis in 1898.

Left: Aubrey Beardsley, The Climax, 1894. Image via Wikimedia Commons; Right: Photo of the painting Medicine by Gustav Klimt, via Wikimedia Commons.

While Beardsley was an untrained prodigy, Gustav Klimt attended the Vienna School of Arts and Crafts (Kunstgewerbeschule) and began his career as the establishment wunderkind. Klimt’s early works, such as his murals for the new Burgtheater in Vienna’s Ringstrasse, fulfilled academic and bourgeois expectations for art with their naturalistic depictions of historical scenes.

But not all of Klimt’s work fit such orthodox constraints. The atmosphere of erotic love and sexuality that pervaded Vienna around 1900 exerted a powerful influence on the artist. Like the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, Klimt saw the artist as a messenger of truth, not fantasy. In 1894, he undertook a commission for murals in the assembly hall of the University of Vienna. Rather than representing the field of Medicine in a logical or sanitized way, as he was expected to do, Klimt portrayed confusion and darkness, knotting together naked bodies and juxtaposing pregnant stomachs with veiled skeletons.

The scandal that ensued ultimately ended Klimt’s academic career, prompting him to found and serve as the first president of the Sezession, the radical Art Nouveau group in Vienna that brought together artists, designers, and architects. They collaborated in the principle of a Gesamtkunstwerk, or “total work of art,” which aimed to be spiritually uplifting through a combination of beauty and utility. Josef Hoffmann’s design for the dining room of Brussels’s Palais Stoclet, which included Klimt’s spiral-filled arboreal murals, exemplified this goal.

It was his iconic portraiture style, however, that earned him a place in art’s historic pantheon. The Kiss (1907), perhaps his most famous work, displays the basic but revolutionary elements of his distinctive idiom: a flattening of form and rich design flourishes within patches of gold leaf applied to the canvas. Representing love as an alignment of surfaces, The Kiss locks the central figures in concentric shapes, entwining lovers’ bodies like jewels in a gold ring. They embrace, a shimmering cloak surrounding them like a membrane, and a wall of flowers falls away. This anxious eroticism for which Klimt is known infused the work of subsequent artists, including his protégé Egon Schiele.

The decorative arts formed another cornerstone of Art Nouveau’s legacy. While France was home to many notable figures—Georges de Feure, Édouard Colonna, and Eugène Gaillard, among others—on the other side of the Atlantic, Louis Comfort Tiffany became the name most associated with the Art Nouveau movement in the United States.

Heir to the silver empire of Tiffany & Co., a company founded by his father, Charles Lewis Tiffany, in 1837, Tiffany started his career as a painter. After studying under George Inness, he began working with decorative art in the 1870s. Supported by enthusiastic patrons in New York, he produced elaborate interiors and complementary metalwork, enamels, lighting, and jewelry.

But Tiffany (as well as his leading competitor, John LaFarge) was best known for an innovative fabrication of leaded glass that became a distinctly American phenomenon. By 1881, his experiments in chemistry had led to the development of glass with an opalescent finish that produced a dreamy, milky quality of light. Surviving features from Tiffany’s elaborate estate on Long Island, Laurelton Hall, reveal his work in full bloom, with windows, ceramic tile, and architectural features coalescing into a garden-like alcove. Staining his glass in an array of colors and adding finely painted details to it prior to firing, Tiffany created a revolutionary look that was hugely successful and allowed the company to expand into the empire of decorative art and jewelry that continues today.

Why Does Art Nouveau Matter?

The success of Tiffany and other decorative artists testifies to Art Nouveau’s goal of tearing down hierarchies between the arts. The rise of print and graphic arts similarly advanced this cause and, unlike Tiffany’s more rarified creations, they could be reproduced to enrich the lives of a broader public. Czech artist Alphonse Mucha’s representations of la femme nouvelle (the bold new woman) are illustrative of the emerging medium of graphic advertisements, as are those of Jules Cheret, whose distinctive Belle Époque designs led to his being considered the father of the modern poster. Even talented painters like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Jan Toorop became as renowned for their graphic art as for their canvases.

Following the vision of Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, architects used steel and other modern materials to create new vocabularies featuring arched and cantilevered forms. The breathtaking Tassel House by Henry van de Velde and Victor Horta, the latter a gifted Belgian disciple of both Morris and Viollet-le-Duc, remains a highpoint of this fluid architectural design. Other outstanding examples came from Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Margaret Macdonald in Scotland; Otto Wagner in Austria; Louis Sullivan in the United States; and the inimitable Antoni Gaudí, known for Casa Mila and Sagrada Familia, in Spanish Catalonia.

Left: Antoni Gaudí, Casa Mila. Photo by deming131, via Flickr; Right: Hector Guimard, Style Metro. Photo by zoetnet, via Flickr.

Art Nouveau bridged an essential gap between 19th-century aestheticism and 20th-century design. Wassily Kandinsky and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, for example, two iconic modern painters, worked in Jugendstil before moving toward their own personal styles. But, just as quickly as it had blossomed across the Western aesthetic landscape, Art Nouveau began to wither in the early 20th century. Ultimately, the movement’s reputation for decadence drove an unintended wedge between wealthy patrons and skilled workers. The flowing, floral character that had once been praised became its liability, leading the English illustrator Walter Crane to condemn it as a “strange decorative disease” as early as 1903. By 1920, the style coup de fouet, or whiplash, had been limply renamed style branche de persil, or sprig of parsley.

—George Philip LeBourdais

Comments

Post a Comment