The Making of Grandma Moses, Folk Modernist

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

The Making of Grandma Moses, Folk Modernist

As she became a commercial success, Grandma Moses was tagged an “outsider” artist — but she emerged “inside” the art world, among modernists.

SHELBURNE, Vt. — The Grandma Moses story reads a lot like an artist’s fairy tale. In 1938, Anna Mary Robertson Moses, a 78-year-old grandmother living on a farm in upstate New York, hung a few of her “old-timey” paintings in a drugstore window. They caught the eye of a New York City art collector, Louis Caldor, who bought them all, plus three more in Moses’s home in Eagle Bridge, New York (about 15 miles from Bennington, Vt.). When he did so, he reportedly told Moses, “I’m going to make you famous.” She and her daughters thought Caldor was crazy.

Moses had no way of knowing that the idea of the pure artist — one who’d not been academically trained, but simply followed her own muse — had seized the imagination of the artistic avant-garde. Modernists would be drawn to Moses’s quaint paintings of steam trains, horse-drawn carriages, and little checkerboard houses dotting patchwork quilt farms. They’ve love how Grandma Moses, as she’d soon be known, recalled childhood memories and relied on her imagination to tell stories.

When Caldor returned to New York City, he showed Moses’s paintings to art dealers and curators. They were afraid to invest time and money in an elderly artist who would soon quit or die. (They could not anticipate that Moses would live and work to age 101.) Sidney Janis, chairman of the Museum of Modern Art’s (MoMA) art committee, took a chance. In 1939, he arranged a one-person, members-only exhibit of Moses’s paintings, which coincided with MoMA’s much-touted exhibiting of “Guernica,” part of the museum’s mammoth retrospective Picasso: Forty Years of His Art.

Was it sheer coincidence that Moses’s show overlapped with Picasso’s? Maybe. Then again, Janis was very savvy and likely knew that MoMA’s members would enjoy the juxtaposition of Picasso with Grandma Moses, a modern “primitive.”

“In France, you have Picasso collecting African art,” says Tom Denenberg, director of the Shelburne Museum in Vermont, giving some context to Moses’s entrance into the art world. “Hamilton Easter Field’s students, in Ogunquit, Maine, were collecting William Matthew Prior paintings, decoys, and weathervanes and putting them in their studios.” In fact, Jackson Pollock attended the Picasso retrospective and, looking at the artist’s flat planes and gestural lines, considered how he could contribute to primitive expression.

“Moses is literally discovered by New York modernists,” says Denenberg, who, with Robert Wolterstorff, director of the Bennington Museum, organizedGrandma Moses: American Modern, on view now at the Shelburne Museum. The exhibit, which includes 60 of Moses’s paintings and works on paper, will travel to the Bennington Museum next year.

Art critics never responded well to Moses, and, in time, as her country grandmother image evolved and she became a commercial success, she would be tagged a “folk” or “outsider” artist. What gets lost in this framing is that she emerged “inside” the art world and among modernists, as this exhibit clearly shows. How many artists, after all, have their first solo show at MoMA? Shortly afterwards, Otto Kallir, founder of Galerie St. Etienne, added Moses to his stable of artists, which at the time included Gustav Klimt, Paul Klee, Oskar Kokoschka, and Egon Schiele.

Knowing this, it’s not so shocking to see Moses’s simply-drawn figures and lollipop trees hanging in this exhibit next to a few works by contemporaries such as Helen Frankenthaler, Hans Hoffmann, Joseph Cornell, and Andy Warhol.

Frankenthaler, also from the Bennington area, painted largely from memory. As Jamie Franklin, curator at the Bennington Museum, writes in the exhibition catalogue, both artists worked fluidly with recalled facts and details. Moses would think back 80 or more years to places she’d been or stories she’d heard; for “The Battle of Bennington,” about a 1777 Revolutionary War clash, she created a colorful and engaging scene that’s more imaginary than factual. In the middle of the painting sits a 306-foot stone obelisk, a monument that would not appear there until a century after the battle. When asked why she placed it there, Moses replied, “it looked good, I guess.”

In a similar way, Frankenthaler drew from her memories of prehistoric cave paintings she had seen in Altamira, Spain, and Lascaux, France. Sometimes she’d refer to postcards she’d collected to jog her memory. Moses used postcards as well, though often in a more hands-on way. For instance, for “Bennington,” she cribbed photographic images of the buildings at the site (originally taken with a fisheye lens) and transferred them, using carbon paper and onion skin, into her landscape. She kept the distortions and black-and-white tones just as they’d appeared in the postcard. Moses made no attempt to be factual or precise. She evoked a myth of country life, back in the old days when her patrons’ grandparents or even great-grandparents farmed these rolling hills and fought the wars.

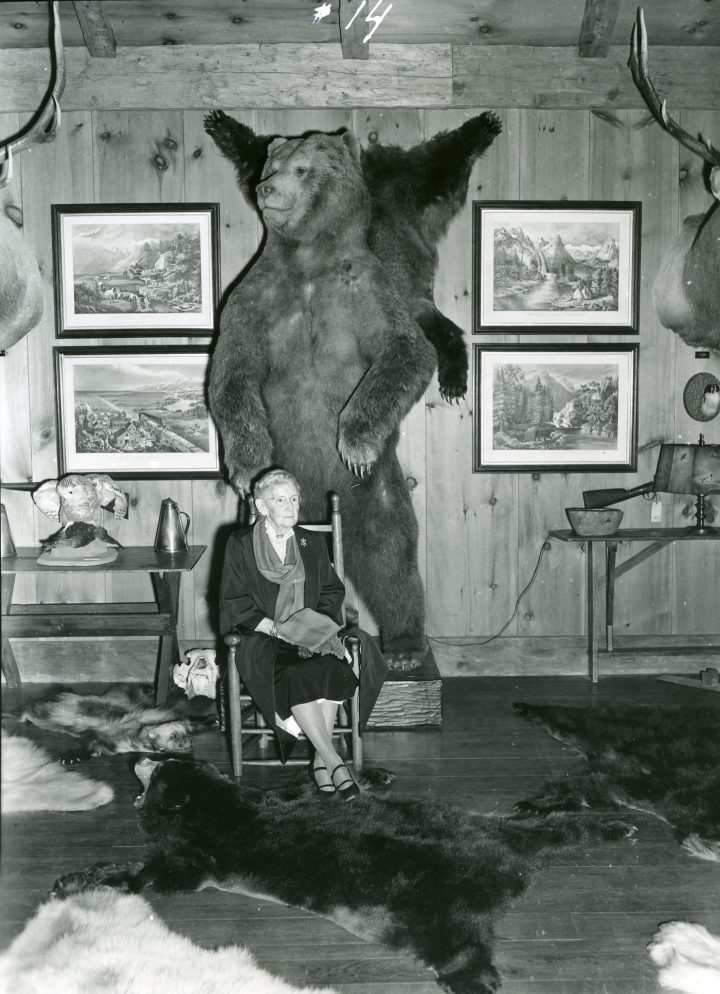

In the catalogue, Diana Korzenik, professor emerita of Massachusetts College of Art and Design, writes about visiting Grandma Moses. She was just seven when the 88-year-old artist asked if she’d like to see her “art secrets.” Moses opened a painted trunk, and inside were magazine clippings, some reproductions of works by Norman Rockwell, Currier and Ives, Luigi Lucioni, and Pieter Bruegel the Younger. Moses traced figures and buildings from these clippings, then collaged them into her paintings.

Joseph Cornell, also a self-taught artist — though considered part of the avant-garde, rather than an outsider — worked in a similar way. He collected clippings of 19th-century figures, such as ballerinas, actresses, and other iconic American imagery, which he cut and affixed directly onto his box assemblages and collages.

“The only difference between what she’s doing and what Cornell is doing, by the 1950–60s, is irony,” says Denenberg. “By the time you get to Warhol, you have this ironic take on the world. That’s the shift from ‘ties-that-bind’ and community sentimentality to modernist thinking.”

What intrigued the modernists about Grandma Moses was that she seemed to emerge from nowhere — a naïve artist, free of training and academic influence. Korzenik, however, questions whether Moses was as untrained as she led everyone to believe. In fact, Moses’s father liked to paint landscapes; he bought her and her siblings paper and taught them some basic skills. Also, when Moses was a child, drawing was part of the curriculum in certain states. For instance, the Massachusetts Drawing Act of 1870 required drawing to be taught in public schools.

Even if Moses had learned a few techniques at school and at home, she did not have formal academic training. Yet “she knows exactly what she is doing” with her art, Denenberg says. “She is coding all this imagery in a folksy way, creating a soothing story for the 1950s of small town life.” After World War II, Americans prospered, the middle class fled to the suburbs, tensions mounted between the US and Russia, and concerns over nuclear attacks rose to the point that schoolchildren were taught to “duck and cover” at their desks. In contrast to this, Moses offered comfort — the simplicity and joy of traditional home and hearth.

She became an international sensation. In 1952, Moses released her autobiography, My Life’s History, which was followed by a television dramatization with Lillian Gish playing the artist’s role. In 1950, Otto Kallir established Grandma Moses Properties, Inc., which offered licensing of Moses’s images for Hallmark Cards, prints, dinnerware, ceramics, and fabrics.

Twelve years later, Andy Warhol painted his “Campbell’s Soup Cans.” Like Moses’s, his work would go on to be turned into every kind of tchotchke imaginable. Warhol delighted in it, because it underscored his message. The organizers of this exhibit wondered how complicit Moses was in spinning her own public image. After careful analysis, Denenberg decided that Moses understood the value in presenting herself as a naïve, folksy grandma and, in doing so, was “very sophisticated in how she controlled the media.”

We see his point in an interview the artist did in 1952, a week after Moses’s 92nd birthday, appearing on the Betty Parry Radio Show for WXKW in Albany. She was dressed in a tailored black suit with a French-designed Lilly Daché hat. When Parry asks the artist to tell stories about the olden days, Moses responds with wit and charm.

She talks about her pictures coming from childhood memories and her imagination, as in “Over the River to Grandmother’s House on Thanksgiving Day Morning.”

“I’ve painted it many times, but no two are alike,” says Moses.

She admits to repeating scenes, but is savvy enough to interject right away that each painting is “unique.”

This escapes the radio host, who merrily responds, “Well, no two Thanksgivings are alike.”

Moses quick-wittedly replies, “And no two grandmas are alike.”

The studio fills with laughter, but there’s a solid truth here. She’s not just a grandma; she’s Grandma Moses. And in this moment, she seems fully aware that there never has been, nor ever will be, a grandma quite like her.

Grandma Moses: American Modern continues at the Shelburne Museum (6000 Shelburne Road, Shelburne, Vermont) through October 30.

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Comments

Post a Comment