Contemporary Aboriginal Australian Art

Journeying Beyond Western Time in Contemporary Aboriginal Australian Art

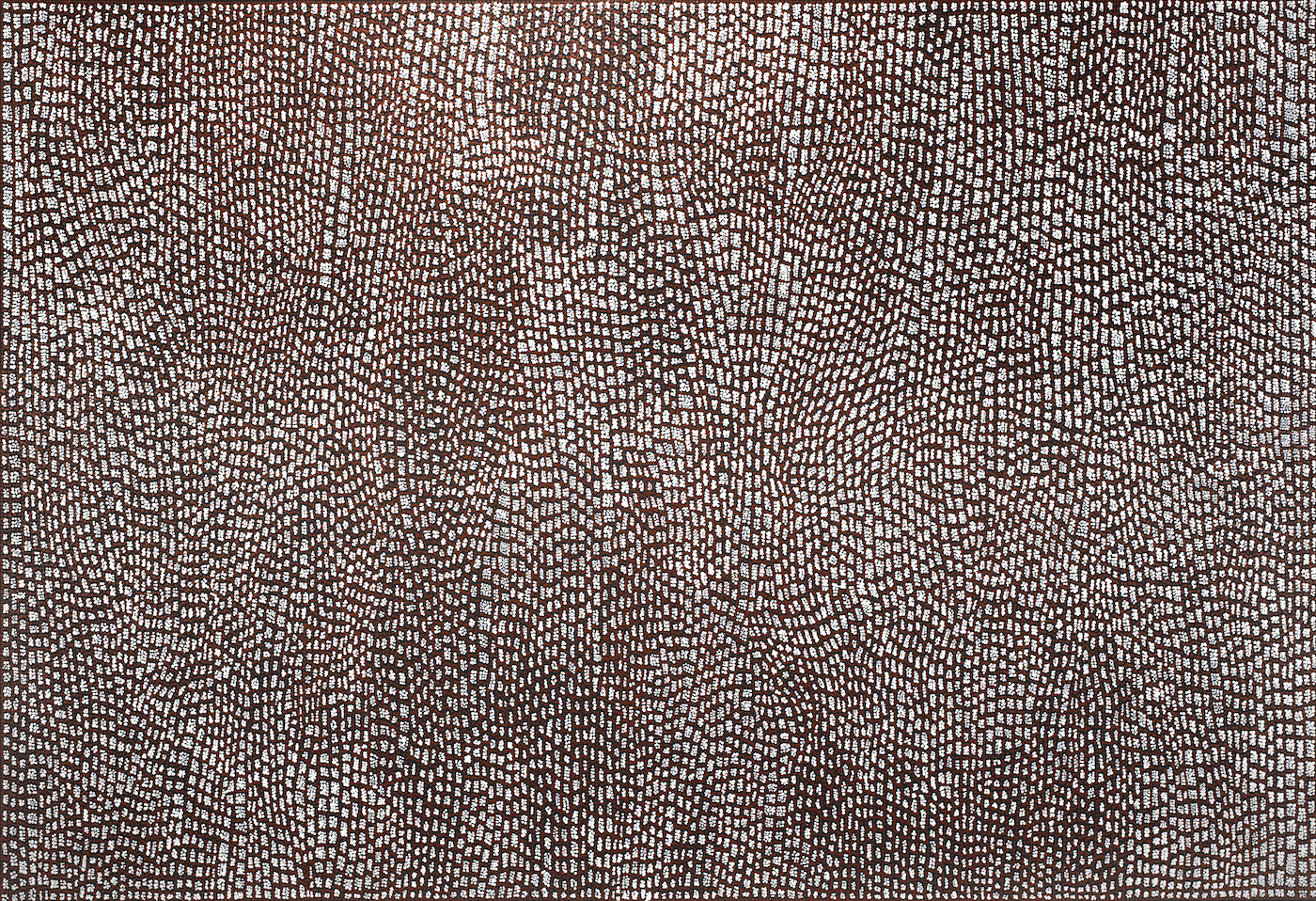

Dorothy Napangardi, “Karntakurlangu Jukurrpa” (2002)

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — In 1971, at a remote government settlement in Australia’s Northern Territory called Papunya, a group of elderly Aboriginal men painted designs from ancestral creation stories onto a school wall in cheap, bright acrylics. They did so at theurging of Geoffrey Bardon, a white schoolteacher, who’d seen these designs in sand drawings and body art. They pictured tribal totems, like the Honey Ant, and other images from ancestral creation myths known as “the Dreaming.”

Australia’s “Indigenous Art Movement” was thus founded by the elders of Papunya — an official “assimilation” center for tribes forced from their traditional lands. Bardon called it ”a community in distress, oppressed by exile, a place of emotional loss and waste.”

This indigenous art, of course, had existed in various forms for most of the 40,000 years of Aboriginal life in Australia — it’s the oldest unbroken art tradition in the world. It just wasn’t visible or marketable to the contemporary Western art industry. Nearly two centuries after the British colonization of Australia, that changed: Indigenous artists of thePapunya Tula collective, like Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri and Kaapa Tjampitjinpa, were showing work at top galleries around the world. Australian-born critic Robert Hughes called it “the last great art movement of the twentieth century,” and it’s continued to evolve into the twenty-first.

Ronnie Tjampitjinpa, “Two Women Dreaming” (1990)

Everywhen: The Eternal Present in Indigenous Art from Australia is one of the most comprehensive shows of work derived from this movement ever presented in the United States. On view at the Harvard Art Museum, it features more than 70 artworks by Aboriginal Australian artists from the past 40 years, alongside “historical objects” from Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. The paintings stand out. Ronnie Tjampitjinpa’s dazzling “Two Women Dreaming” (1990) is composed of four concentric rectangles in yellow, black, and white that evoke two pairs of hypnotized eyes. Dorothy Napangardi’s “Karntakurlangu Jukurrpa” (2002) is a shimmering curtain of white dots on a bronze background that is meant to illustrate the rocky topography of the Tamani desert. Walter Tjampitjinpa’s “Rainbow and Water Story” (1972) is one of a handful of original paintings from Papunya on view.

Most works here offer abstract interpretations of “the Dreaming,” or “Tjukurrpa,” an archive of stories about the world’s creation by ancestral beings. Central to these narratives is an understanding of time as a cyclical and circular order. “One cannot ‘fix’ the Dreaming in time; it was, and is, everywhen,” wrote Australian anthropologist William Stanner.

“For more than a century, Indigenous people have been defined and confined by Western colonial constructions of time,” the gallery’s wall text reads. “This exhibition offers a corrective: an opportunity to be immersed in an Indigenous sense of time.” Unfortunately for the Western viewer — perhaps especially for the professionally busy, goal-oriented Harvard University student viewer — shifting your “sense of time” isn’t as simple as looking at a painting; if it were, hallucinogens wouldn’t be so popular on college campuses.

Walter Tjampitjinpa, “Rainbow and Water Story” (1972)

Works like Tommy Watson’s “Wipu Rockhole” (2004) might pull you into a kind of dream state. With speckled amoeba-like blobs surrounded by magenta and green snaky squiggles, it depicts rockholes in the artist’s grandfather’s country. But even if these paintings do transport the viewer into “the eternal present,” they grow fraught when placed back into the more linear timeframe of post-colonial Australian history and the global art world. According to exhibition curator Stephen Gilchrist, who’s of the Yamatji people of the Inggarda language group of western Australia, half of all artists in Australia self-identify as indigenous. But many feel their work, like their broader culture, is trivialized or exploited by the Eurocentric Australian art establishment.

“Australia espouses the existence of native people through its romanticism of Aboriginal art — and the idealism of Aboriginal art — and projects that into the world. But it’s just the art, it’s not the people,” Vernon Ah Kee, one of the artists featured in the exhibit, said in a recent interview with WBUR. “It’s worth a lot of money, but the money doesn’t go back to the people who actually make it.”

Tommy Watson, Wipu Rockhole (2004) (Image © Tommy Watson/Courtesy of Yanda Aboriginal Art) (All images courtesy Harvard Museum of Art)

Australia consistently ranks as having one of the highest standards of living in the world, but that standard doesn’t usually apply to Aboriginal people. Like Native Americans in the US, indigenous Australians have shorter life expectancy, poorer health, and lower levels of education and employment than non-Indigenous Australians. In 2008, the Australian government made a formal commitment to addressing Indigenous disadvantage, called “Closing the Gap,” and have made some amends for historical oppression and violence towards indigenous people. But so far, these efforts have led to only minor improvements. And on a cultural level, many artists feel that discriminatory attitudes towards Indigenous Australian art, such as the stereotype of Indigenous styles as “primitive,” persist. “We exist in Australia as a kind of non-people,” Ah Kee said.

Emily Kam Kngwarray, “Anwerlarr angerr (Big yam)” (1996)

The absurdity of characterizing these Indigenous works as “primitive” or somehow “other” becomes especially pronounced when you compare them to the past century of “modern” Western art. Take, for example, the similarities between “dot paintings” like Tommy Watson’s “Wipu Rockhole” (2004) and Yayoi Kusama’s wild speckled canvases, like “Give Me Love.” Rover Thomas, one of the first indigenous Australian artists to gain recognition by the mainstream global art market, was annoyed when he came across a painting in a museum by Abstract Expressionist Mark Rothko: “‘That bugger paints like me,’” he told Gilchrist. Until his death in 1998, Thomas painted muted, earthy color fields, such as “Yari Country,” which is in the exhibition. Emily Kam Kngwarray’s “Anwerlarr angerr (Big yam)” (1996), a wormy cluster of pink, yellow, and white squiggles on black, looks like a cousin of American painter Brice Marden’s tangled loops. Such similarities are coincidental — the styles were developed independently and the meanings of the works are vastly different in context. Though “Yair Country” echoes Rothko’s work in form, it’s actually a reflection of an ancestral narrative of a man burning to death during a drought.

Rover Thomas, “Yari Country” (1989)

While the paintings dazzle, the exhibit’s wall texts tend to breeze over the fraught history and current plight of Indigenous Australians. (Pondering this plight certainly makes it harder to connect with “the eternal present.”) In one wall text, we read of the “Great Australian Silence,” a term coined by anthropologist William Stanner to describe white Australians’ efforts to avoid conversation about the “dispersion” (an awpolite term for murder) of Indigenous people.

“Many Lies,” an installation by Vernon Ah Kee, condemns this silence in a poem printed diagonally across the gallery wall. The text evokes feelings of erasure and frustration at perceived revisionist history in Australia. “Many lies have been told about me,” it begins. “I wrote the lies down/but that didn’t make the reason for the lies any clearer to me/and I am left bewildered and confused.”

It’s a luxury to go from strolling an ivy-covered crimson campus to absorbing the “Indigenous sense of time” illustrated in these vibrant paintings. But without sufficient historical context, the average non-Aboriginal Australian viewer’s understanding of this art will also be, at best, bewildered and confused.

Everywhen: The Eternal Present in Indigenous Art from Australia continues at Harvard Art Museums (32 Quincy Street, Cambridge, MA) until September 18.

Comments

Post a Comment