a chunk of lapis lazuli is currently on view in the The Painter on Display, a small rotating installation on the identity of artists and their materials.

Lapis Lazuli: A Blue More Precious than Gold

Giovanni Battista Salvi da Sassoferrato, “The Virgin in Prayer” (1640–50), oil on canvas, with lapis lazuli pigment on her clothing (via National Gallery, London/Wikimedia)

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — The first blue pigment to hold its color was often prized over gold. The semi-precious stone lapis lazuli was ground into an iridescent pigment, sometimes called ultramarine, that seemed to shine when applied to the canvas. The first known use of it as a pigment goes back to 6th and 7th century BCE wall paintings in Bamiyan, Afghanistan, the country where almost all of the lapis lazuli used in art was mined. It became especially popular in Renaissance Europe, often used to accent the robe of the Virgin Mary, the hue simultaneously telegraphing a high price, and a purity of material.

At the Harvard Art Museums in Cambridge, Massachusetts, a chunk of lapis lazuli is currently on view in the The Painter on Display, a small rotating installation on the identity of artists and their materials. Organizer Lola Sanchez-Jauregui, a Maher curatorial fellow in American art, stated in an online post: “It’s important not to overlook this material side of painting. I hope that viewing these tools will help people approach the paintings from a new point of view.”

Installation view of ‘Artists and Their Tools’ at the Harvard Art Museums (photo by the author for Hyperallergic) (click to enlarge)

The stone is joined by an animal skin bladder from the late 18th or early 19th century, the pre-paint tube used by artists to seal paints with string or ivory tacks and prevent them from drying, as well as a vial of powdered lapis lazuli. This container of pigment is in the Forbes Pigment Collection, an archive of rare pigments that’s part of Harvard’s Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies. It went on public view when the Harvard Art Museums reopened in 2014 (as covered by Hyperallergic). The rows of glass bottles arranged according to the color wheel are visible from the top floor through the central glass atrium. Edward Waldo Forbes, director of the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard from 1909 to 1944, amassed these precious pigments with a pioneering interest in conservation.

Senior Conservation Scientist Narayan Khandekar told Hyperallergic in 2014: “It was put together by Edward Forbes in an attempt to understand the material nature of works of art, and that approach to understanding art had not been taken before. It was the beginning of the scientific approach for conservation in the United States.” By studying the pigments, conservators could better understand the degradation of color in art, especially when materials like lapis lazuli became effectively obsolete thanks to new synthetic pigments.

Forbes Pigment Collection in the Harvard Art Museums (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Stepping back a few centuries, why was lapis lazuli so incredibly valuable, and why were artists and patrons willing to spend so much on a single color? That expense gave these works an incredible prestige, especially as the material had to travel a long distance on the same routes as the spice trade. Plus, it already had an illustrious history as a stone, used on the sarcophagus of King Tutankhamen, on a headdress buried in the Sumerian tomb of Queen Puabi, and, legend goes, as eyeshadow by Cleopatra.

The pigment emerged in Europe in the 14th century, and its regal status endured. Johannes Vermeer, for instance, used it much more extensively than his 17th-century contemporaries. As the National Gallery explains, aside from “unifying the overall colouristic effect, its distinctive presence may have subtly enhanced the perceived value of the paintings for collectors.” In his 1670–72 “A Young Woman Seated at a Virginal,” lapis lazuli brightens the curtains, highlights the shadows on her arms, and mixes with green earth on her dress for a lush and light turquoise. The turban on his enigmatic subject in the 1665 “The Girl with a Pearl Earring” is also luminous with the ground semi-precious stone.

Johannes Vermeer, “The Girl with a Pearl Earring” (1665), oil on canvas. Lapis lazuli was used on the blue of her turban. (via Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis/Wikimedia)

Michelangelo, “The Last Judgment” (1536-41), fresco. Lapis lazuli was used in the blue of the sky (viaSistine Chapel/Wikimedia)

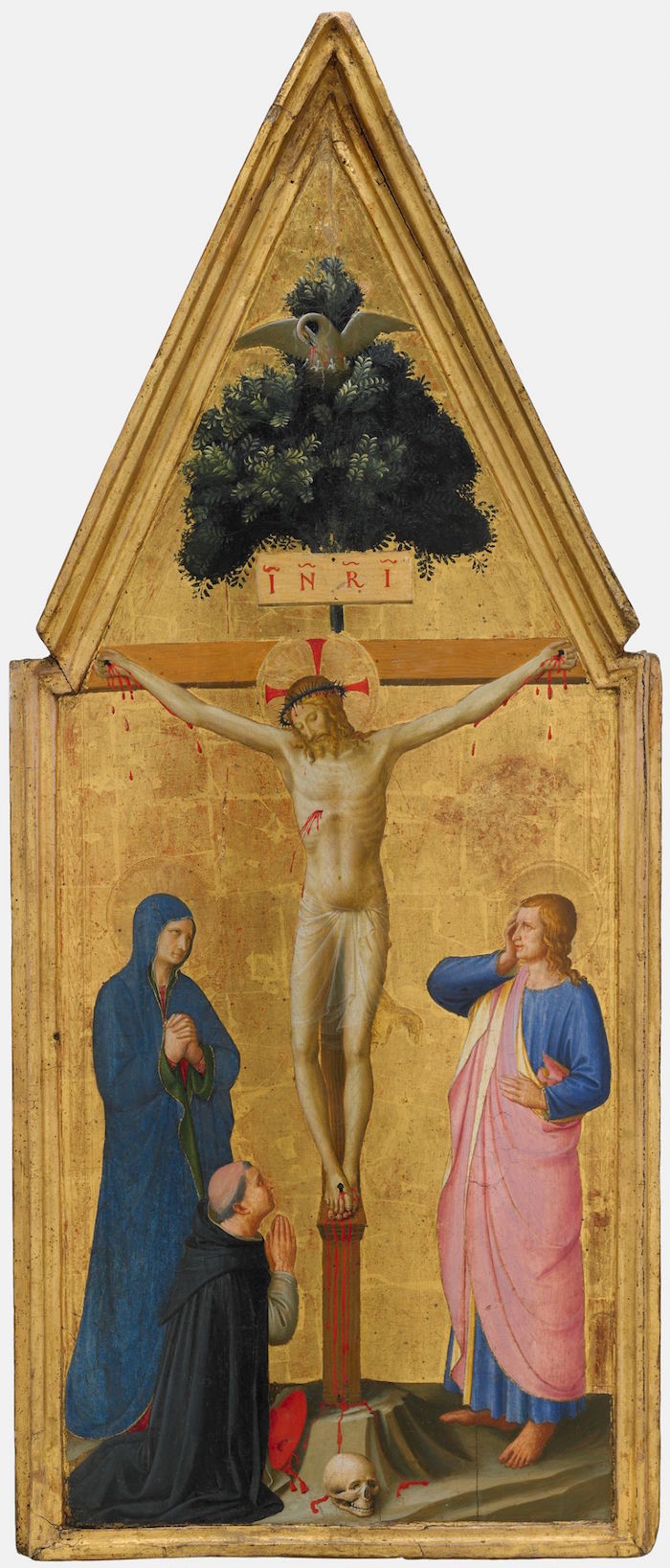

Vermeer followed artists like Fra Angelico who created dazzling religious icons in the 15th century (lapis lazuli is still sometimes called “Fra Angelico blue”), and Michelangelo, who used the Vatican coffers to order huge quantities of it for his 1536–41 “Last Judgment” fresco in the Sistine Chapel. Around the same time, Titian illuminated his 1520–30 “Bacchus and Ariadne” with a lapis lazuli blue sky and wind-blown garments on his mythical figures.

In a 1797 etching included in The Painter on Display at Harvard Art Museums, James Gillray satirizes Old Master-obsessed artists like Benjamin West and Robert Smirke in “Titianus Redivivus.” The illustration references a young woman who falsely claimed she knew Titian’s secrets and would share them at 10 guineas a pop. One of these secrets was his incredible use of color, helped by the glow of lapis lazuli.

The aura of the radiant color still endures, even since it emerged in a synthetic form in 1826. For example, the International Klein Blue by artist Yves Klein gets its punch from a heavy use of the ultramarine pigment. The little bottle of blue with the craggy rock in the Harvard Art Museums’s rococo and neoclassicism gallery is not a monumental display by any means (quite the opposite), and the frenzy for the pigment has largely faded. However, it’s still a coveted commodity. The Guardian reported in June that illegal mining of the blue stone is supporting the rise of the Taliban in the province of Badakhsan, long the primary source of this lustrous color. Even as its significance in art has faded, lapis lazuli remains a valued natural resource, its possession representing power.

Titian, “Bacchus and Ariadne” (1520-23), oil on canvas. Lapis Lazuli was used in the sky and draped garments. (via National Gallery, London/Wikimedia)

Johannes Vermeer, “A Young Woman Seated at a Virginal” (1670-72), oil on canvas. Lapis lazuli was used in the curtain, to highlight the woman’s arms, and mixed with green earth for the blue-green of the dress. (via National Gallery, London/Wikimedia)

Fra Angelico, “Christ on the Cross, the Virgin, Saint John the Evangelist, and Cardinal Torquemada” (1453-54) (courtesy Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Hervey E. Wetzel Bequest Fund)

Pietro Perugino, “Polittico della Certosa di Pavia (Vergine col Bambino e angeli)” (1500), with lapis lazuli used in its blues (via National Gallery/Wikimedia)

Forbes Pigment Collection in the Harvard Art Museums (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Installation view of ‘Artists and Their Tools’ at the Harvard Art Museums (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Comments

Post a Comment