ANDRE MASSON - THE ABSTRACT SURREALIST....

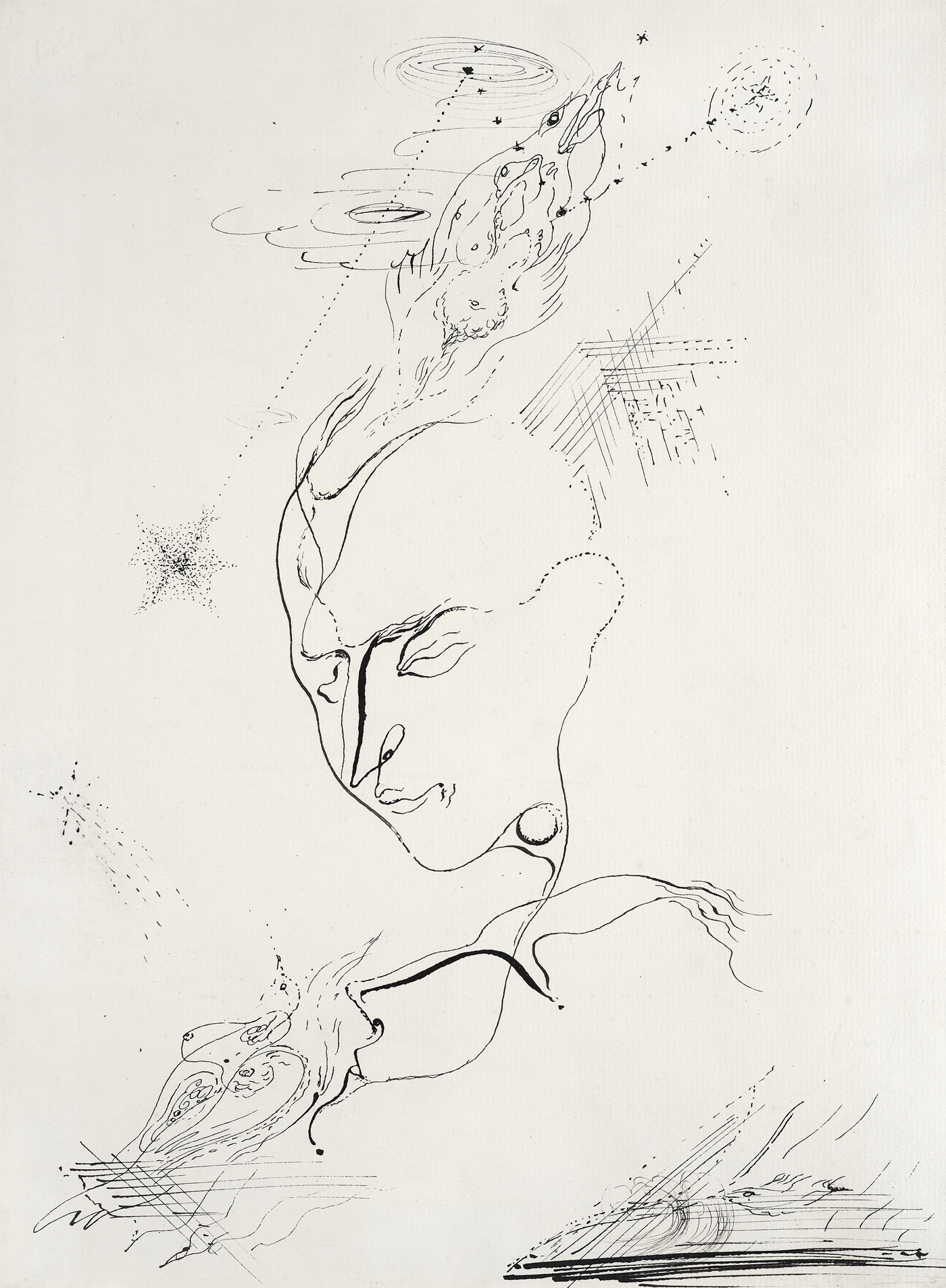

André Masson, “La mer se retire” (“The Sea Withdraws,” 1941) (all images courtesy Galerie Natalie Seroussi) (click to enlarge)

PARIS — In the polyvalent and multilayered drawings of André Masson, you can sense a free hand in love with its own movement, but not with itself. There is a speeding, automatic, ritualistic, and revelatory mode of iconographic mark-making in all the drawings in André Masson dans l’antre de la métamorphose at Galerie Natalie Seroussi, which seem to flow from one key piece: the sex-machinic “Automatic Drawing” (1924). This jittery work sets up a conflict between hard angles and the feminine litheness of curves. Aggressive lines cut through the supple curves of a centered, nude woman made of Francis Picabia-like cyborg parts. The drawing evidences an artistic method that plays on the line between chaotic control and non-control, aiming toward a capricious alliance that likens mechanical grinding to organic sexuality, an association that opens up both notions to mental connections that enlarge them. In this work, the subsequent cyborg woman of Fritz Lang’sMetropolis (1927) is already undone by disturbances she cannot contain.

An expanded field of subjects pervades the visual lexicon of Surrealism, but Masson is generally considered to have pioneered the automatic drawing technique with an opulence that borders on the decadent. Masson’s graphic automatism was a visual analogy to the écriture automatique, a writing method based on speed, chance, and intuition. In doing so, he also revealed a certain amount of reflection and artistic strategy.

However, around the exact same time (summer of 1924), the English artist and chaos magician Austin Osman Spare — a late-decadent, perversely ornamental graphic dandy in the manner of Felicien Rops and Aubrey Beardsley — produced a sketchbook of “automatic drawings” featuring disembodied fabula on a par with Masson’s. Entitled The Book of Ugly Ecstasy, it contained a series of outlandish, pan-sexual creatures produced through automatic and trance-induced means. This swank book was purchased by the art historian Gerald Reitlinger, but in the spring of 1925 Spare produced another, similar volume, A Book of Automatic Drawings, which has been reproduced. Spare claimed to have been making automatic drawing as early as 1900 (when he was 14), yet he was unknown to the Surrealists. Nevertheless, the dates of his automatic drawing books parrallel Masson’s semi-automatic drawings “Benjamin Péret — Automatic Drawing” (circa 1925) and “A Louis Aragon” (1924) in uncanny ways. Masson’s beautiful, drowsily drawn “Benjamin Péret — Automatic Drawing” fluidly depicts the French poet. Like Spare, Masson began automatic drawings with no preconceived composition in mind. Like a medium channeling a phantom spirit, he let his pen travel hastily across the paper without conscious control, soon finding hints of images emerging from the abstract, lace-like web.

Like Masson, Spare claimed that twisting and interlacing lines permit the magical germ of an idea in the unconscious mind to express — or at least suggest — itself to consciousness. For Masson, artistic intentions should just escape consciousness. Although some shapes are discernible amid abstract lines, others seem to be open to interpretation, allowing viewers to use their own subconscious cues to decipher the images. In time, shapes might be found to emerge, suggesting forms.

Masson’s drawing “A Paul Éluard” (1924) has a dream-like, dilettante quality to it, as the fluid but broken lines seem to move the eye between one partial figure-object and the next, almost as if the objects were being swept down a rowdy river. Perhaps it demonstrates what Gertrude Stein once quoted Masson as saying about himself: “what Stein called ‘the wandering line’ is probably a key characteristic of my work. But it wasn’t the line that was wandering, it was me.” I think this wounded, wandering line explains why Masson’s automatic drawings varied in style, but continued to reflect the horrors of war on the human psyche. A wounded veteran of World War I, Masson was plagued by a post-traumatic stress disorder that became so severe that he was habitually hospitalized for it.

The intense “Dessin automatique” (1924–25), which is almost erotic, strikes hard as an example of the divinatory practice of finding subconscious desires within vague cues. It is a neurotic network of lines that seem fluid but hectic, at times even staccato-like. Gradually appearing might be a standing, plugged-in burial casket surrounded by phantasmagorical figure motifs that may include object parts merged with anatomical fragments. The sum total gives off a feeling of occultist ferment. Like many of Masson’s drawings, it is really a site of suggestibility full of the duality of violence and whimsy. It alludes to several potential meanings rather than giving one. Often, as in one of the weaker drawings at Galerie Natalie Seroussi, “Dessin automatique” (1925), Masson left traces of the rapidly drawn ink mostly visible so that they extend to the mind a hypothetical flexing, allowing the viewer to probe the opaqueness of the world and discern concealed forces.

As the show moves through the 1930s on into the ‘40s, one can follow Masson’s line drawings as a form of non-linear thinking. “Mélancolie du Minotaure” (“Minotaur’s Melancholy,” 1938) has the empty, open, opium-inflected, desert-like space and bull thematics readily identified with mainstream Surrealist painting, and thus appears rather conventional for Masson. His relations with André Breton had first deteriorated in early 1927, when he felt Breton’s brand of Surrealism becoming something binding like religion, and in 1928 he rejected the collective project called for in the second manifesto. “La ville cranienne” (“The Cranial City,” 1939) is a delicately colored complex of mental confusion that is much less typical. It is a joyful drawing, and masterful.

However, my favorite piece from this era is the really bizarre “Le génie de l’espèce” (“The Genius of the Species,” 1939), a tortured celebration in the Nietzschean tradition of the self-contradictory premise. But for the hairy ladder, it looks as if Masson began drawing this chaotic hybrid figure with no preconceived subject or composition in mind. (The Museum of Modern Art owns a drypoint version of this odd rapture; it is an entangled configuration, holding an egg, that seems to have emerged from the landscape of the unregulated id.)

“La mer se retire” (“The Sea Withdraws,” 1941) is another virtuoso display of convoluted forms, one made up of mercurial symbols apparently withdrawing from their role as steady representation. Masson’s balletic drawing “Maldoror” (1937) is less spontaneous and pre-rational than many of the drawings here. Masson’s visual discord compels us to take notice of the various ways that art conventions mold our responses. In “La mer se retire,” I sense a play with visual homophones — between the French words for sea (mer) and mother (mère) — as a compositional device to trigger a multifarious narrative of disturbance. This work, as opposed to “Maldoror,” more deeply enmeshes, hinders, alters, and disrupts elementary visual communications with chimerical games of hide and seek. By creating iconographic tensions, “La mer se retire” — like “Le génie de l’espèce” — might also be seen as the product of Masson’s specific aesthetic doctrine, which appeared to favor conflicting forms. Both works reminded me of what Félix Guattari said inChaosmosis: An Ethico-aesthetic Paradigm, that “art, for those who use it, is an activity of unframing, of rupturing sense, of baroque proliferation or extreme impoverishment which leads to a recreation and a reinvention of the subject itself.”

Installation view of ‘André Masson dans l’antre de la métamorphose’ at Galerie Natalie Seroussi (click to enlarge)

Robert Motherwell once suggested that Abstract Expressionism should have been called “Abstract Surrealism.” If this aesthetic connection had been made, it would have been due largely to Masson. It is well documented that Jackson Pollock was fascinated by the Surrealist idea of a spontaneous, automatic transfer of internal feelings into compositions that are practically arbitrary. The automatism of Masson offered Pollock an opportunity to depict the negation of figuration. Indeed, in the November 1959 issue of Arts Magazine, William Rubin — later the director of the painting and sculpture department at MoMA — drew just such parallels in a comparison of Pollock and Masson.

To be sure, each era has its redundancies and its compliances, but the chaotic excess of Masson’s automatic drawings plays well into today’s widespread cravings for unlimited information, which connected technological flow tends to encourage. In the informational abundance of Masson’s images, transmission was already the endpoint.

André Masson dans l’antre de la métamorphose continues at Galerie Natalie Seroussi (34 Rue de Seine, 6th arrondissement, Paris) through July 31.

Comments

Post a Comment